Middle and high school teachers in Florida put on their sea legs, boarded the R/V Weatherbird II, and conducted science that matters to their students and communities.

Dr. Teresa Greely (L) assists C-IMAGE Chief Scientist Leslie Schwierzke-Wade (middle) as she talks with 3rd graders at Jamerson Elementary in Florida during a Skype ship-to-shore video conference. (Also pictured is scientist Heather Broadbent). (Photo by: Mary St. Denis)

Educators worked with scientists to understand the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. While gaining hands-on experience, teachers blogged and Skyped to share their learning and have others virtually join their adventures. Back on shore, teachers created classroom materials.

The Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem (C-IMAGE) research consortium, led by the University of South Florida, hosts a Teacher at Sea Program. C-IMAGE expeditions collect marine data – from sea-surface plankton to deep-sea microbes in sediments – to answer questions about long-term oil spill impacts and understand the Gulf system.

This year’s participants were Matt MacGregor (Escambia High School), Mary St. Denis (Winter Haven High School), Elisabeth McCormack (Dunedin Highland Middle School), and Kathryn Bylsma (Dr. John Long Middle School). Their blogs depict life at sea and the academic rigor and challenges that go into planning and implementing sea experiments.

Below are a few highlights from their sea expeditions. Read more at the C-IMAGE blog Adventures at Sea: Deep Sea Fish and Sediment Surveys in the Gulf.

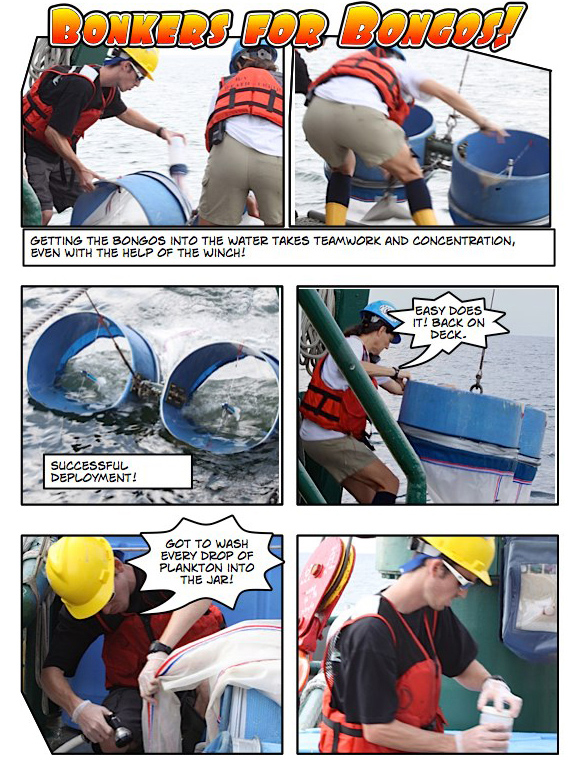

Teacher Elisabeth McCormack created a humorous way to share science with students. (Image provided by C-IMAGE)

Gung Ho! Enthusiastic Teachers

Teachers eagerly await their time at sea. Mary St. Denis said, “It is an exciting countdown to an adventure…to get out in the field and do science is a dream spot for many teachers like me.”

Some teachers expressed their enthusiasm through creative cartoon-style story-telling. Elizabeth McCormack created a skit filled with “characters” (real people on the vessel) and “action” (their at-sea research). Check out her Bonkers for Bongos blog !

Dr. Kendra Daly, the C-IMAGE chief scientist on the vessel was happy to have them: “The teachers were enthusiastic, hardworking, and valuable members of the science team.”

All Aboard! A Community of Active Learners

Impressive science teams are on board and their work of discovery and learning resonates with teachers, as Kathryn Blysma explains, “I am blessed to be surrounded by so many people who are avid learners… from such incredibly varied backgrounds… microbiology college students, European engineers, and graduate volunteers who enjoy…putting their skills to good use. It’s when there are interactionsbetween communities that true learning takes place.”

Teacher Matt MacGregor (R) and FWC scientist and graduate student, Matt Garrett prepare Niskin bottles in a CTD system. (Photo by: Teresa Greely)

That community spirit of learning and doing fosters teamwork. Blysma saw this as teams worked from early morning gathering data to late nights analyzing it: “This group has a real system down, a kind of bucket brigade where everyone takes a job or a section to be responsible for.”

Part of the learning involves sea technology. This year, C-IMAGE tested the SIPPER 4 (Shadow Image Profiler and Evaluation Recorder), a small “Rubik-cube size” underwater high resolution camera that goes deeper than earlier devices. It takes pictures of plankton and collects data on physical conditions. McCormack said the most exciting part was its internet connection ability, “That means engineers do not have to snag a spot on a research vessel to access the data, but can work with it in their lab thousands of miles away!”

College students are on board and they gave teachers insights on the value of hands-on learning. Blysma wrote about Joe, an undergraduate student, who had no interest in school until he went to an environmental center in his district. There, his whole outlook on learning changed. “[This] reminded me that each child we see is a ‘Joe’ searching for his niche. As teachers we are the wayfarers nudging and encouraging them at stages in that venture.”

All Hands on Deck! STEM in Action

Teacher Mary St. Denis (R) filters water with Dr. Teresa Greely (L) at the lab onboard the R/V Weatherbird II. St. Denis said, “My students and I are very concerned about the effects of the Gulf Oil Spill. I am really happy to be a part of finding out more about what is happening in the Gulf.” (Photo provided by C-IMAGE)

C-IMAGE conducts interdisciplinary science to understand Gulf marine ecosystems. McCormack described how science, engineering, and technology came together with the SIPPER 4, “A scientist may know what they want to measure, but it may take the mechanical mind of an engineer to build the device that can collect that data.” Marine technicians got the equipment in and out of the water, completing a demonstration of collaborative efforts among specialists.

Teachers experienced the evolving nature of science discovery when a routine task – collecting bottles of seawater – took on greater importance, becoming as McCormack said “one of the most important missions on this cruise.” They found one sample from deep Gulf waters that looked and smelled different and determined that it contained much less salt than water from that depth does normally.

They hypothesized about freshwater sources, including the Mississippi River outflow into the Gulf. Scientists will run additional tests at their home labs and look for an explanation. McCormack said, “I feel really lucky I was out here in the Gulf when we had a mystery to solve…I got a chance to see how all of this fits together.”

Field work reminded teachers that answering big questions requires a systematic process that takes time. McCormack said they could not start with “What happened to the Gulf after the oil spill?” explaining that “It is too broad, and impossible to answer with a single measure.” She likened it to eating a steak in one bite instead of pieces and explained that the scientific method includes collecting data many times and in multiple ways before tackling the difficult job of interpreting it. “But in the end,” said McCormack, “you have data that means something….You find answers to your questions and are inspired to ask new questions and start all over again.”

Ship-to-Shore! Connecting Future Scientists

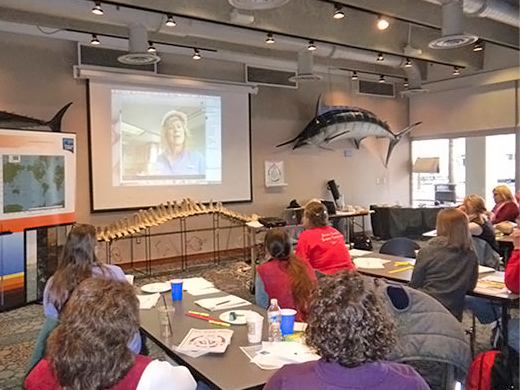

Dr. Teresa Greely (on screen) Skypes with educators during a professional development session at the New England Aquarium during IODP Expedition 340 in the Lesser Antilles. (Photo by: Jennifer Collins, Deep Earth Academy, COL)

C-IMAGE scientists use Skype to visually and verbally share their scientific missions in real-time with the K-12 community. One online demonstration was with 90 third graders at Jamerson Elementary School in St. Petersburg, Florida. They toured the boat, saw researchers retrieve bongo nets and collect plankton samples, and spoke with science experts and crew members. St. Denis marveled, “So far this week, about 370 students have virtually sailed with us.”

Teachers in the field make an impression on students, “Wow, Miss McCormack, you really have done a lot of stuff!” McCormack reflected on this important revelation, “My goal is to encourage students to both observe and interpret the world around them…to get out there and see real science happening.” She continued, “I love bringing authentic data sets to the math classroom so I can give students an answer to their ‘why do we need to learn this” questions.’”

Educators’ use of social media grabs students’ attention. One teacher described her class’ response to a Skype session: “They got a kick out of us using Skype!…It really hit home that it is a useful tool for ‘real’ work and not just socializing!”

Dr. Daly noted that the teachers “worked around the clock,” but “still found time to create blogs and communicate with their students. We were fortunate to have such wonderful volunteers.”

Bounty! Helping the Gulf

In the midst of all the bustling ship and research activities, teachers maintained a bigger-picture perspective. Reflecting on the “bottle of seawater” mystery, McCormack connected that specific experience with a larger purpose: “Scientists have systematically collected these samples over the past three years [and] have begun to create a historical database that will allow us to develop a clearer picture of how the Gulf behaves over time.”

Blysma wrote about the importance of connecting her experience with making future generations prepared to help the Gulf: “What does all this have to do with the Deepwater Horizon event or the data being collected? It’s the study of human impact on the environment and the critical balance that has to be maintained.”

For more information about the C-IMAGE Teacher at Sea Program, contact Dr. Teresa Greely. To learn more about the Florida Institute of Oceanography’s R/V Weatherbird II, take a virtual tour.

This research was made possible in part by a Grant from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) through theCenter for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem (C-IMAGE) consortium. The GoMRI is a 10-year, $500 million independent research program established by an agreement between BP and the Gulf of Mexico Alliance to study the effects of the Deepwater Horizon incident and the potential associated impact of this and similar incidents on the environment and public health.