Estuarine marshes in coastal Louisiana face numerous threats such as sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, and contamination threats such as oil spills that can lead to marsh loss and changing habitats. Ben Aker collects insects from different habitats within coastal marshes and assesses their abundance and biodiversity. His research will help identify potential marsh health indicator species and generate baseline data for future research into marsh loss and habitat restoration efforts.

Ben is a master’s student with the Louisiana State University AgCenter’s Department of Entomology and a GoMRI Scholar with the project A study of horse fly (Tabanidae) populations and their food web dynamics as indicators of the effects of environmental stress on coastal marsh health.

His Path

Ben’s interest in science was fueled by the passionate professors he met as a biology undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin Whitewater. “I’ve never talked to a professor who wasn’t enthusiastic about their research, and I want to have a similar level of excitement about my work,” he said. Ben pursued a degree in ecology, evolution, and animal behavior and conducted undergraduate research on the distribution of predatory robber flies. He is continuing entomology research as a Louisiana State University master’s student studying coastal insects and their salinity-related distributions with Dr. Lane Foil and Dr. Claudia Husseneder’s coastal insect ecology team, which studies Deepwater Horizon impacts on Louisiana marshes.

“I want to use interesting organisms to help answer important ecological questions,” said Ben. “Our research seeks to highlight the importance of coastal insects and their potential use as tools for marsh conservation and ecological research.”

His Work

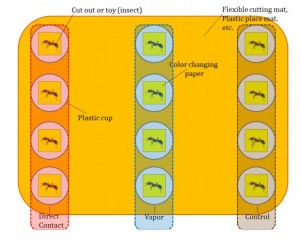

Ben’s research examines plant and insect biodiversity along salinity gradients using data collected during a year-long study (July 2018 – June 2019). He focuses on 18 Louisiana marsh sites in Barataria Bay and Caillou Bay designated as either low-, mid-, or high-salinity based on historical data. Using sweep nets, he collects insects monthly and identifies each insect to the family level. He also assesses average ground cover, dominant plant life, and biodiversity differences between salinity levels at all sites. He then uses the EstimateS biodiversity software to determine biodiversity in areas with different salinities and creates a rarefaction curve for each salinity level. Rarefaction curves plot the number of families observed in relation to the sample size and the estimated total families to determine if a sampling effort can sufficiently assess diversity.

Preliminary results from data collected during the first five months show that each salinity level had differences in overall plant composition, but Spartina cordgrass species consistently dominated ground cover (Spartina patens at low- and mid-salinity sites and Spartina alterniflora at high-salinity sites). Chironomids (non-biting midges) were the most abundant insect family at low-salinity sites but were replaced by Delphacids (plant hoppers) as salinity increased. Results from the insect biodiversity indices suggest that family-level biodiversity decreased with increasing salinity. Further sampling is required to adequately assess insect diversity, which will come as Ben processes the remaining data. “Overall, we captured a conservative estimate of approximately 89.3 – 99.3% of families present,” explained Ben. “This high percentage of families collected is expected to increase as we complete a full year of sampling.”

Ben utilizes his research findings to identify potential bioindicators of marsh health. He observed that most insect families appeared at all salinity levels and that only rare species were unique to a single salinity level. Since rare species are inefficient bioindicators, he instead uses a specificity measure (how well the potential bioindicator predicts the salinity level) and a fidelity measure (how likely it is that the potential bioindicator will be encountered at that salinity level) to associate insect families with different salinities. So far, he has associated fifteen insect families among the different salinity levels and combinations of salinity levels.

“It is likely that these insect families are associated with [certain] salinities due to life cycle requirements or herbivory of specific plants,” said Ben. “For example, two families associated with low-salinity sites (Chironomidae and Coenagrionidae) have aquatic juveniles to which higher salinity levels may be detrimental, and a family associated with high-salinity sites (Blissidae) is represented in our collection by a single species that feeds primarily on Spartina alterniflora.”

Ben is currently identifying members of the associated bioindicator families to the species level. He and Co-Principal Investigator Dr. Claudia Husseneder will conduct DNA barcoding on key species within indicator families, which will allow students or researchers with minimal taxonomic training to easily identify important insects for future coastal studies. The insect inventory generated by Ben’s research also provides comparative baseline data that researchers can use to observe how insect communities change following stress-induced marsh loss or following marsh recovery resulting from habitat management.

His Learning

Dr. Foil’s multidisciplinary background showed Ben that being well-read across multiple fields could help him contextualize his research in the greater picture. He put this concept into practice at the annual Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science (GoMOSES) conference, which facilitates interdisciplinary and cross-institutional collaboration. “The most important aspect of the GoMRI science community to me is the ability to interact and cooperate with other GoMRI associated labs,” Ben said. “Following the 2018 GoMOSES conference, I participated in a Seaside Sparrow workshop with the Taylor and Stouffer labs from Louisiana State University’s School of Renewable Natural Resources (see Smithsonian Highlights CWC Research on Seaside Sparrows). Because they focus on the Seaside Sparrow diet, I am providing a DNA barcode database of salt marsh insects to compare their samples against.”

His Future

Ben plans to pursue a Ph.D. and continue his insect and ecology-related education. He advises students considering a scientific career to take statistics and scientific writing courses when they are available, “It’s easy to focus just on the research occurring in your specific field and overlook the importance of study design and being able to communicate your results.”

Praise for Ben

Dr. Foil praised Ben’s ability to adapt to challenging work conditions. He explained that Ben did as the locals do to handle the brutal heat and harsh conditions (hats, sunscreen, hydration, seeking shade) during two-day biweekly boat trips to collection sites, implementing two collection strategies, and sorting thousands of insects. While baseline animal population data prior to Deepwater Horizon was severely lacking, Dr. Foil said that Ben and his fellow graduate students are addressing these gaps using various techniques that mix DNA sequencing with classic taxonomy. “Saltwater intrusion and fresh water diversions are inevitable in the changing coastal habitats,” said Dr. Foil. “Hopefully, Ben will provide valuable data for use in evaluating these effects on biological communities.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Ben Aker and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

By Stephanie Ellis and Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact sellis@ngi.msstate.edu for questions or comments.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2019 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).