The Alabama Center for Ecological Resilience (ACER) blog hosted a series of posts discussing the meaning behind various terms and concepts that are important to ACER research.

The Alabama Center for Ecological Resilience (ACER) blog hosted a series of posts discussing the meaning behind various terms and concepts that are important to ACER research.

The Deep Sea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (Deep-C) Consortium released a series of publicly available and easy-to-read fact sheets detailing their scientific research and outreach initiatives:

Science: Deepwater Corals

What are corals? Where and how do they live? What are the threats to Gulf corals? Click here to download.

Science: The SailBuoy Project

Experimenting with a new marine device used for scientific observations in the Gulf of Mexico. Click here to download.

Science: Deepwater Sharks

Information about the bluntnose sixgill shark, one of the most common species in the Gulf. Click here to download.

Science: Tiny Drifters – Plankton

What are plankton? Why are plankton important? How did the oil spill affect Gulf plankton? Click here to download.

Science: Oil-Eating Plankton

Naturally occurring microbes in the ocean feed on the hydrocarbons in oil. Click here to download.

Science: Oil Fingerprinting & Degradation

What is oil? How does oil “weathering” occur? And what can oil samples tell us? Click here to download.

Outreach: Gulf Oil Observers

Deep-C’s citizen scientist initiative connecting high school students to ongoing oil spill research. Click here to download.

Outreach: Scientists in the Schools

Interactive visits to middle school classrooms by Deep-C scientists and educators. Click here to download.

Outreach: 2015 Annual ROV Training & Competition

Students from middle and high schools vying for ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) domination. Click here to download.

Marine protists are single-celled planktonic creatures that form the base of the marine food web and perform important ecosystem services, including driving photosynthesis and the carbon and nitrogen cycles. Protist communities include energy-producing organisms, such as phytoplankton, that use sunlight or chemical reactions to generate their own food. Protists also include predators, such as microzooplankton, that eat the energy-producing protists.

After Deepwater Horizon, research found that spilled oil significantly lowered phytoplankton abundance and shifted the community species composition from ciliates and phytoflagellates to diatoms and cyanobacteria. Researchers also observed that chemically dispersed oil reduced the abundance of certain ciliate microzooplankton species that feed on energy-producing protists. Understanding how concurrent oil spill effects and altered predator-prey interactions influence these bacterial communities could help spill responders and ecosystem managers anticipate algal blooms and food web changes.

Chi Hung “Charles” Tang conducts oil exposure experiments on protistan predators and producers to examine how oil and dispersant affect their ability to carry out ecological functions and support the food chain. His findings will help determine the oil or dispersant concentrations that impact the growth and grazing interactions of Gulf of Mexico protist communities.

Charles is a Ph.D. student with the University of Texas at Austin’s Department of Marine Science and a GoMRI Scholar with the Dispersion Research on Oil: Physics and Plankton Studies III (DROPPS III) consortium.

His Path

As a biology undergraduate student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Charles conducted a senior research project that investigated the changing temporal and spatial patterns in phytoplankton community composition across a southern China estuary. Charles measured the physicochemical conditions of seawater, collected phytoplankton samples, and used statistical analysis to examine environmental drivers, which deepened his interest in the ecology of planktonic organisms.

Charles completed a biology master’s degree at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and began searching for a Ph.D. program studying phytoplankton and microzooplankton ecology. He read about Dr. Ed Buskey’s research on the relationship between Texas brown tides (algal blooms) and zooplankton grazing and asked Dr. Buskey about potential graduate research opportunities. Dr. Buskey felt that the GoMRI-funded oil spill research that he and his team were conducting was a perfect fit for Charles and would allow him to develop his own research focus. Charles joined Dr. Buskey’s lab as a graduate researcher investigating oil’s influence on microzooplankton grazing.

His Work

Charles began his research using outdoor mesocosm experiments that exposed natural protist communities containing both producers (phytoplankton) and predators (microzooplankton) to dispersed crude oil. He determined rates of producer growth and predator grazing after two and six days of exposure. While microzooplankton’s grazing habits consumed ~40-60% of the energy that producers generated daily under normal conditions, he observed reductions in producer growth and predator grazing after two days of exposure. After six days, however, he observed recovery in producer growth but a continued reduction in predator grazing, suggesting that predator communities may be more susceptible to oil exposure than producers.

“My findings suggest that, because oil impacts their natural predators more severely, the less-susceptible phytoplankton producers may have a chance of unchecked proliferation, which could potentially lead to algal blooms under certain conditions,” explained Charles. “Additionally, the reduced feeding and, therefore, reduced growth of the protistan predator community could lead to reduced food sources for organisms at higher trophic levels, such as larger zooplankton, larval fish, and bivalves.”

Charles’s current experiments examine how different oil and dispersant concentrations affect the population growth of both producers and the ingestion rate of predators and the prey. He conducts laboratory experiments that incubate protistan predators and producers separately under short- (24-hour) and long-term (days) exposure to environmentally realistic oil and dispersant concentrations that resemble conditions near the sea surface following an oil spill. His short-term experiments examine how crude oil alone, dispersant alone, and crude oil plus dispersant (20:1 oil to dispersant, the application ratio used during Deepwater Horizon) affect protistan predator grazing. Long-term experiments examine how crude oil plus dispersant concentrations ranging from 1 to 30 µL/L (reflecting conditions observed following Deepwater Horizon) affected the population growth of predators and producers.

Charles uses a compound microscope to observe prey ingestion and population growth and estimate the median inhibitory concentration (IC50, the concentration that causes a 50% drop in protistan population growth) of chemically dispersed crude oil for protistan species, which reflects their sensitivity to oil pollutants. He also applies DNA sequencing to determine which microorganisms are present in the water samples at the different time points, which can help him characterize how protistan predators feed on producers in oil-polluted water. “Since producers can be very tiny and morphologically indistinguishable, DNA sequencing can help identify what types of bacteria are present in oil-loaded seawater,” explained Charles. “Although bacterial producers are subject to grazing by small protistan predators, some producers can consume carbon and other components from biodegraded oil as an alternative food source and can therefore grow rapidly when oil is spilled in the water column.”

Charles is still collecting and analyzing his data, but his preliminary results suggest that grazing by protistan predators was significantly reduced at high concentrations of chemically dispersed crude oil (10 µL/L) when compared to control treatments. He hopes that his findings provide key evidence that will help us better understand the consequences of oil spills on marine ecosystems.

His Learning

Charles speculates that he may not have been able to conduct his self-developed experiments without Dr. Buskey’s mentorship and financial support. Dr. Buskey’s support for Charles’s projects taught Charles that scientific research is greater than one researcher and requires a dedicated and collaborative team. He experienced this collaboration on a larger scale at the annual Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science conference, where he met other GoMRI scientists to exchange ideas and identify new research methods. “I share the values of the GoMRI science community to improve our ability to understand, respond to, and mitigate the problems caused by petroleum pollution,” he said. “The conference is a good opportunity for us to collaborate and work together towards our goals.” He plans to seek a postdoctoral position, so that he can continue conducting marine science research.

Praise for Charles

Dr. Buskey explained that Charles’s hard-working personality shone when he faced and successfully worked through several challenges beyond his control, including the laboratory’s closures following Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and the ongoing COVID-19 response. Dr. Buskey said, “We recently learned that Charles is a recipient of the highly competitive Continuing Fellowship from the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School for summer 2020. Congratulations, Charles!”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Charles Tang and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the DROPPS website to learn more about their work.

By Stephanie Ellis and Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact sellis@ngi.msstate.edu for questions or comments.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2020 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

The Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal published an article that describes how scientists are using the In Situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System (ISIIS) to photograph zooplankton organisms and gather information about salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and light levels. The detailed imagery that the ISIIS collects is helping researchers understand how incidents such as Deepwater Horizon may affect the microscopic organisms that live in the Gulf of Mexico’s dynamic coastal waters, where biomass and plankton are highly concentrated.

Read the article What the Big Picture Can Teach Us About Tiny Ocean Creatures featuring scientists Adam Greer and Luciano Chiaverano (University of Southern Mississippi Department of Marine Resources and the Consortium for Oil Spill Exposure Pathways in Coastal River-Dominated Ecosystems or CONCORDE). They describe how biologic data is combined with physical oceanographic modeling to track zooplankton, make links to important fish species and coastal processes, and improve understanding of the shelf ecosystem.

Read these related stories:

By Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact maggied@ngi.msstate.edu with questions or comments.

************

GoMRI and the Smithsonian have a partnership to enhance oil spill science content on the Ocean Portal website.

The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2019 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

Adam Boyette retrieves a glider on the deck of the R/V Point Sur, where he served as chief scientist on the three-day cruise examining the impacts of the Bonnet Carré spillway opening. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Microscopic organisms called plankton, an important component of the marine food web, congregate in the freshwater-laden coastal waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Adam Boyette wants to learn more about how and where these plankton live to better understand how an oil spill or other disaster might impact their populations.

He is collaborating with other scientists to show how the near-coastal environment interconnects with the larger world around it.

Adam is a GoMRI Scholar with CONCORDE working towards a Ph.D. in marine science at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM). He discusses his journey from the Mississippi Delta to the coastal Gulf he now calls home.

His Path

Adam stands by on the deck of the R/V Point Sur to retrieve the CTD rosette. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Adam grew up in a rural town at the heart of the Mississippi Delta, an area made famous by Muppets-creator Jim Henson and blues music. He spent his childhood outdoors collecting insects and snakes, fishing, and exploring the Delta’s rich ecology.

His first visit to the Florida panhandle at age eight sparked a life-long love of the ocean that would eventually steer his future.

Adam did not begin college immediately after high school. Instead, he worked on Mississippi River tow boats and in catering kitchens, discovering new interests and skills in every job. He would earn a bachelor’s degree in marine biology at USM more than ten years after he graduated from high school, immediately complete a master’s degree in marine science, and then move on to his Ph.D.

“I had this unfulfilled yearning to do something meaningful, something where I could contribute,” Adam said, explaining that living through the one-two punch of Katrina and the oil spill deeply affected him. “You want to be part of something bigger than you are. I knew without a doubt that I wanted to be a marine scientist.” Adam joined several research cruises while working as a graduate assistant for ECOGIG co-principle investigator Vernon Asper, including the successful effort to rescue the downed AUV Mola Mola. Familiar with GoMRI’s mission, he jumped at the chance to join CONCORDE director Monty Graham’s lab when the consortium formed in 2015.

His Work

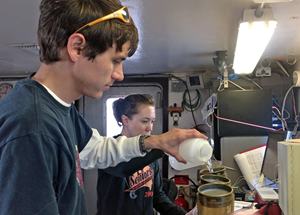

Adam takes notes in the R/V Point Sur’s lab while his FlowCam analyzes samples. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Adam studies the thin layers of plankton common in the coastal Gulf of Mexico water column. He measures the plankton’s photosynthesis processes to better understand their uptake and primary production rates of carbon. He also investigates how frequently other organisms, namely predatory microzooplankton, graze on these plankton concentrations. This information will help researchers understand how pollutants like oil move through the area and what living creatures they impact.

Adam collects seawater within the Mississippi Bight, a coastal environment dominated by river water plumes that mix and merge with the salty Gulf. He has joined other CONCORDE scientists on three larger research cruises and sampled on his own in small crafts. “When I’m not actually on a research cruise, I’m either preparing to go on one or analyzing data from a previous one,” he laughed.

Adam determines carbon uptake rates in his samples using an incubator called a photosynthetron, which simulates the in situ light environment and uses the resulting vertical light gradient to measure photosynthetic rates. He uses this information to calculate plankton’s carbon production and uptake and to estimate changes in phytoplankton abundance and growth over a 24-hour period.

Adam works on dilution experiments during the early morning hours of a cruise. (Provided by Adam Boyette)

He also conducts experiments to examine grazing rates for microzooplankton feeding on phytoplankton. Then, he runs the samples through a particle imaging device called a FlowCAM to identify organisms in the water, allowing him to determine how many and which plankton and predatory microzooplankton species live in his study area.

Adam uses this information to understand the dynamics of nearshore microbial populations during various seasons. His calculations will be incorporated into a large ecological model that CONCORDE scientists are creating to represent the physical, chemical, and biological processes in the nearshore environment. “My motivation is to understand the connectivity between all things, to show how delicate the interplay is between the world we see and the microbial world,” he explained. “It’s a personal fascination.” Adam’s raw data collected through his CONCORDE research are available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative (GRIIDC).

His Learning

“As Dr. Graham’s student, I’ve learned a lot about working collectively to achieve a common goal,” Adam said. “He’s provided wonderful leadership opportunities for emerging scientists to learn and grow.” One such opportunity came earlier this year, when Adam served as the chief scientist on an emergency three-day multi-consortia cruise to study the Bonnet Carré spillway opening, an action taken to protect New Orleans from rising Mississippi River floodwaters that sent millions of gallons of freshwater into the northern Gulf. He and other GoMRI scientists attending the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science Conference discussed how the unusual event might impact their study areas and planned the cruise.

Adam and fellow graduate student Naomi Yoder teach Pontchartrain Elementary students about nearshore ecology during an Earth Science Day event. (Photo by Stephanie Watson)

The cruise included scientists from CONCORDE, DEEPEND, ECOGIG,CARTHE, and ACER. Adam took pleasure in seeing the process through from its somewhat chaotic inception to a highly organized research event, drawing on his experiences working in professional kitchens to keep everything running smoothly. The array of cross-disciplinary GoMRI scientists also helped make the project a success. “The most important thing I learned from this experience was to let go,” Adam said of his chief scientist position. “Put your trust in people and don’t try to be in control of everything. Instead, work with everyone and utilize their expertise – these people are here for a reason.”

His Future

Adam plans to finish his doctoral program in May 2018. He wants to continue researching plankton ecology using technologies such as satellite imaging and the FlowCam. His dream is to become an ongoing water quality project manager working for government agencies such as NOAA or the EPA or in a postdoctoral role at a university. “The oil spill has really shown the importance of long-term datasets,” Adam said.

Adam and fellow USM student Liesl Cole work in the R/V Point Sur’s highly secure radioisotope lab (known as the “rad van”) during the CONCORDE Spring Campaign. (Photo by Heather Dippold)

Praise for Adam

Monty Graham serves as both CONCORDE’s principle investigator and the Director of USM’s School of Ocean Science and Technology. He stated, “I can attest to Adam’s maturity, leadership potential, technical skills, and motivation and am thrilled that he is being recognized for his efforts.” Graham called Adam a critical member of the CONCORDE project, “He has been the student that his peers look up to, and a student that my research colleagues seek for advice. He pursues every opportunity to increase his knowledge within his chosen field, and has learned new technologies that are going to be applied widely in our studies.”

Graham explained that Adam shines in leadership roles, receiving “stellar reviews” from everyone involved in the Bonnet Carré cruise. “He has led his fellow students through trainings and scientific discussions and he is respected by his peers and senior scientists alike,” said Graham. “He is an excellent addition to the GoMRI Scholar program and is the definition of student success.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Adam Boyette and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the CONCORDE website to learn more about their work.

************

This research was made possible in part by a grant from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

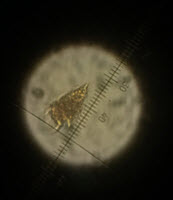

Deep-C_Cruz_MicroscopeIMG_0537-web-225×169.jpg” alt=”Jarrett Cruz examines nannoplankton samples under a microscope. (Photo provided by Jarrett Cruz)

Jarrett Cruz has been all over the world studying nannoplankton, a marine species he did not know existed when his journey began. Jarrett’s research into these minuscule creatures spans both biology and geology as he studies the impact of oil on nannoplankton that live in the Gulf of Mexico.

Jarrett, a geology Ph.D. student at Florida State University’s (FSU) Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science, is a GoMRI Scholar with the Deep-C consortium.

His Path

Jarrett took a high school career aptitude test, and the result of “scientist” surprised him. He laughed in disbelief, “I thought, ‘I’m never going to be a scientist!’” He enrolled as a criminology major at FSU, intending to become a police officer like his older brother but changed to biology after the first lab, which peaked his interest. He thought medical school would be his next step, and he continued that path since nothing else really appealed to him. However, things changed when Jarrett took a geology class taught by Dr. Sherwood Wise.

Jarrett separates nannoplankton from seawater samples. (Photo provided by Jarrett Cruz)

“The last semester of my bachelors I met Dr. Wise and began working for him in the Geology Department,” Jarrett explained. “He introduced me to nannofossils, nannoplankton, and the Deep-C project. I felt as though I finally found what I was looking for.”

He minored in geology, extending his biology undergraduate study to work more closely with Wise. Jarrett participated in five research expeditions on the R/V Bellows during that year and collected water and sediment samples for several Deep-C teams. The project’s focus on phytoplankton dovetailed perfectly with his biology background and his current study of nannofossils. He got such a good start on his research that he completed his master’s work in geology in just one year.

Jarrett recently returned from two months on the Indian Ocean, where he served as a nannofossil specialist with the Integrated Ocean Discovery Program, an international group that studies ocean floor geology, on the Drilling Vessel JOIDES Resolution. He used that experience to begin collecting data for his Ph.D.

His Work

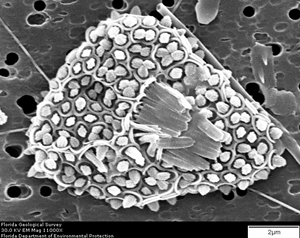

A microscopic image of Navilithus altivelum, one of the species that Cruz studied. (Photo provided by Jarrett Cruz)

Jarrett has been recording the numbers and location of various nannoplankton species for five years. Nannoplankton can be found in all parts of the Gulf, but he focuses on those living in the photic zone, around 200 meters depth in the Gulf of Mexico. Very little baseline data exist for these populations, so the team is documenting seasonal variation and rare species as part of their research on oil impact and recovery of plankton. Jarrett said, “No one has ever done a quantitative study of nannoplankton through seasonal changes like this for the Gulf of Mexico.”

Nannoplankton are so small that they slip through standard plankton nets, so Jarrett extracted them from water and sediment samples. He filtered out anything larger than 50 microns using strainers. Then, using nucleopore filters, Jarrett isolated the nannoplankton and dried them while on board before transporting the collections to FSU for laboratory analysis.

Jarrett continued his work in the lab, cutting out sections of filters, attaching them to stubs using carbon tape, and then coating them with gold palladium. He observed his samples in a scanning electron microscope and counted the tiny disk-like plates (coccospheres) that nannoplankton shed. He made these counts by observing 200 different fields of view and identifying nannoplankton species encountered. Finally, he analyzed the resulting large data set to locate shifts in assemblages or species throughout the study interval.

One of the things Jarrett most enjoyed about his biology and geology work is time at sea. (Photo provided by Jarrett Cruz)

The team observed shifting numbers in diversity and abundances of nannoplankton cells from year-to-year. However, total increases in biomass and diversity seemed to show a recovery from the Deepwater Horizon spill over the four-year study interval.

While working on his nannoplankton survey, Jarrett made a remarkable discovery – finding Navilithus altivelum, a species only seen off the coast of Java in the Indian Ocean. “This find is particularly interesting because it brings to light how rare and diverse some of these oligotrophic species are,” said Jarrett.

His Learning

“There are questions in life you want to explore and answer,” Jarrett said. “That’s what research is, and it’s pretty amazing.”

Jarrett credits Wise and the Deep-C team with giving him the opportunity to answer questions and expand his abilities in other areas, particularly in speaking and writing. Saying that Wise is adamant that a good scientist must be a good communicator, Jarrett found himself regularly pushing his public speaking comfort zone. He worked as a teacher’s assistant and joined Wise at public outreach meetings and research conferences to present their findings. These events turned Jarrett from young man who had never flown on an airplane before college to an experienced world traveler, going to places such as Crete, Sri Lanka, and Singapore.

“My trip to Crete stood out because I presented my publication on a species observed in the Gulf that had never been spotted in the western hemisphere,” Jarrett said. “I actually got to hang out with the person who originally named the species, so that was a treat.”

His Future

Jarrett’s recent trip to India kick-started his Ph.D. research. He is also assisting with the publication of an Atlas of Coccolithphores and Diatoms in the Gulf of Mexico. The International Nannoplankton Association recently named him as an officer, which he called a great honor.

He plans to get industry experience this year, working with Bugware Incorporated on oil drilling operations. As an operations team member, Jarrett will look at the nannofossil assemblages to determine sediment age. His fossil analysis will help the drill operators choose the best equipment to get safely through sea floor.

Recently engaged, Jarrett plans to marry in the near future. After completing his Ph.D., he would like to stay in academia, perhaps continuing his research and teaching. He hopes to inspire others the way Wise inspired him.

Praise for Jarrett

Dr. Wise described Jarrett as a go-getter, full of energy and always on the move. According to him, Jarrett was a natural leader for the Deep-C project, “His undergraduate biology major was a perfect background for this work, which was a totally new experience for the rest of us with traditional geology degrees.”

Wise said that Jarrett’s transfer to study geology was seamless, “Jarrett is putting his GoMRI experience to good use toward his doctorate degree.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Jarrett Cruz and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

************

This research was made possible in part by a grant from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) to the Deepsea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (Deep-C) consortium.

The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.