Alek stands next to a map of his research area, holding the drift cards he used in his oil spill study in front of a nautical chart of the Salish Sea. (Provided by Alek)

Fueled by a passion for science and endangered species, Alek designed and executed a research project that involved scientists from eight institutions, four-hundred drift cards, and over a year’s work. A substantial undertaking for any scientist, this is even more impressive because Alek is seven years old.

Alek Finds a Calling

Alek lives in Washington near the coast where he has spent much time watching and learning about orca whales, specifically the Southern Resident Killer Whale of which there are about eighty known remaining.

“I really like the white eye patches they have,” he said. Scientists at the Center for Whale Research near Alek’s home are working hard to track and protect these orcas. “Dr. Ken Balcomb is the main whale researcher there,” said Alek. “He inspires me because he stands up for these whales’ freedom and protection.”

A copy of the first two pages of Alek’s hand-written letters asking for donations to fund his research in the form of an “Adopt a Drift Card” campaign. (Provided by Alek)

When Alek was five, he read a book that discussed the environmental impacts of the Deepwater Horizon and Exxon Valdez oil spills, which drove his desire to help protect the ocean ecosystem near his home. “My heart broke because it was so sad,” he recalled. “The whole ocean ecosystem was contaminated for hundreds of miles, and lots of ocean animals died.” Every year, thousands of oil tankers cross the Salish Sea, an intricate network of coastal waterways near the United States-Canadian border where many of these whales live. Alek became concerned that the Southern Resident Killer Whales could encounter and be affected by large amounts of oil if a spill occurred.

A Little Help From His Friends

Alek began gathering books on oil spills and visiting university research websites when he was six, focusing on oceanography departments that study spills.

A hand-drawn map that Alek included in his fundraising letter shows oil tanker routes in the Salish Sea. (Provided by Alek)

He emailed scientists around the country, including Piers Chapman and Tamay Özgökmen – the directors of the GISR and CARTHE consortia, respectively – for input on how to proceed. More than ten prominent researchers agreed to sit on Alek’s science committee and advise his research.

Alek chose to conduct a drift card study after finding out it would take more than a year to obtain a permit to deploy GPS-enabled drifters, an ocean current tracking method that he wanted to pursue like Özgökmen has done. Drift cards, made of wood or other lightweight materials that float on the water’s surface, are another tool that can show how currents move through an area. Chapman has used drift cards, deploying them at a fixed location and plotting times and points on a map where people report cards they discover (the cards have printed explanations about their purpose and reporting instructions). As Alek’s project developed, Chapman and Özgökmen answered his questions and reviewed his reports.

“Alek is an incredibly motivated young man,” said Chapman. “I was very happy to suggest possible ways that he could analyze his data while putting his report together and make suggestions to help give the video he made about his research more impact. He’s a great kid and deserves every encouragement.”

Alek paints his drift cards bright yellow using a non-toxic, biodegradable paint mixture. (Provided by Alek)

Alek’s family was supportive and helped him with the things he couldn’t do himself, such as traveling to various sites and using an electric saw to cut wood into drift cards. However, they encouraged Alek to raise the money needed for the project himself so that he would get a broader experience of being a scientist.

Alek sent letters asking people to sponsor a drift card for one dollar per card. He collected $460 from donors across the country, including many scientists, and even received a letter from President Obama thanking him for his work. He used this money to purchase biodegradable and nontoxic materials to build the cards.

If You Build Them, They Will Drift

Alek releases his finished cards in Rosario Strait between Peapod Rocks and Buckeye Shoals—one of the busiest oil tanker routes in the Salish Sea. (Provided by Alek)

Alek made two batches of 200 cards, each batch labeled either “A” or “B.” He deployed the cards at Rosario Strait, a dangerous channel that many ships pass through on their way south. He released the first set on September 6, 2014, as the tide was going out and the second set as the tide was coming in on September 21. Days and weeks went by, and one-by-one people in the area returned 181 drift cards. He even received information about one that had floated all the way to Alaska! He calculated the GPS coordinates where each card was found, logged them into a spreadsheet, and used this information to populate maps on Google Earth.

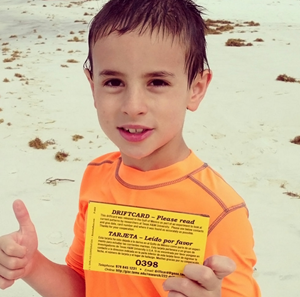

Some people who found drift cards sent Alek a photo of the card they found. Within four months, 45% of Alek’s drift cards had been found and reported. (Provided by Alek)

Alek then mapped the probable path oil would take through the Salish Sea should a spill occur in the Rosario Strait. He compared these paths to reports of orca migrations to show where their paths might encounter oil. “The orcas don’t know how to avoid oil in water, so they would swim right through it,” said Alek. “It is sad to find out that, if my oil spill simulations were real, every single one of the endangered orcas here would be at risk of oil contamination.”

When he completed his study, Alek created a website about the project. The site contains an overview of his work with maps, charts, and graphs showing his findings and suggestions for what the public and lawmakers can do to reduce our dependence on oil and protect endangered species. No one from congress has responded yet, but many others have, including Jane Goodall who sent an email praising his efforts to call attention to these whales’ potential risk. Alek also created a short video summarizing his study, a one hour video detailing his project, and a 154-page scientific report.

This person sent Alek a picture of himself and the drift card he found. (Provided by Alek)

“I was so impressed by Alek’s one-hour movie of his year-long study—the level of detail was amazing,” reflected Özgökmen. “We are looking at a hardworking, brilliant young mind here. I can only hope that he gets the best education this country can offer, as he will have much to contribute to our society in the future.”

Alek’s Perseverance

Alek admitted that creating the spreadsheets and maps was more work than he expected. After several months of data entry and analysis, there were times when he felt like giving up because of the work volume.

Alek proudly shows off his data spreadsheets. He has promised to share his data, analysis, and maps with other scientists and research groups to help support their environmental studies. (Provided by Alek)

However, he said that instead of quitting, he looked to the great scientists of history to remind himself to keep going, “I thought: What if they gave up? If Copernicus gave up, we might never know the sun was the center of the solar system. If Charles Darwin gave up, we might not know about evolution. If Crick and Watson gave up, we might not know how genetics and DNA work. I learned I couldn’t give up, because everything that is important in life takes hard work!”

This Google Earth map shows the differences in estimated contamination areas one week after oil is released under an outgoing tide (red) and an incoming tide (yellow). (Provided by Alek)

What’s next on Alek’s radar? He sees “endless possibilities” for more science in his future. “Some of the things I am thinking about are chemistry, building an underwater ROV, and 3D printing,” he said. He also stated that, although still many years in the future, he hopes to study marine science in college. One thing is certain: whatever direction he eventually pursues, Alek has already proved himself a precocious scientific thinker in the world of oil spill research.

This Google Earth map shows the estimated area at risk of oil contamination four months after the simulated spill. (Provided by Alek)

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.