Marine ecosystems provide many valuable resources for humans, including seafood and petroleum. Conservation policies that protect marine ecosystems, especially pollution and petroleum-related policies, depend on accurate scientific data about the ways different marine species experience pollution. Madison Schwaab quantifies levels of toxic oil compounds in the bile and tissues (liver, muscle, and gonad) of fifteen pelagic Gulf of Mexico fish species to better understand how oil affects them compared to other species.

Madison is a master’s student with the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science and a GoMRI Scholar with the Center for the Integrated Modeling and Analysis of Gulf Ecosystems III (C-IMAGE III).

Her Path

Madison spent her childhood catching fish and blue crabs with her father on Chesapeake Bay, where she witnessed firsthand how human activities can negatively affect rivers, bays, and oceans. These experiences piqued her curiosity about quantifying those impacts. As a Temple University undergraduate student, she worked in Dr. Erik Cordes’ deep-sea ecology lab investigating how ocean acidification impacts cold-water coral physiology. She also worked at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center studying the behavioral avoidance of inland silversides in hypoxic and acidified environments. These research experiences showed her how changing conditions can negatively affect marine and estuarine animals.

Madison wanted to conduct anthropogenic-related research and started researching graduate programs in Texas and Florida, where she knew there was ongoing oil spill research. The oil spill research conducted in Dr. Steve Murawski’s Population and Marine Ecosystem Dynamics Lab at the University of South Florida intrigued her, and she reached out to him before applying for a graduate research position there. He invited her to visit during a recruitment weekend, and she immediately clicked with the lab and the university. She joined the group as a master’s student conducting GoMRI-funded research quantifying petrogenic and pyrogenic contaminant concentrations in pelagic fish.

Her Work

Madison sampled fifteen pelagic tuna and billfish species collected as by-catch during benthic research cruises (2011 – 2017) and main catch during a pelagic cruise (2018). Because the collection includes different time points and regions, she compared differences in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) concentrations between these pelagic species and across different regional, spatial, and temporal scenarios. She also used data compiled by her fellow C-IMAGE researchers to compare PAH concentrations in the pelagic species with species living in other ocean habitats.

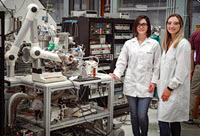

Madison analyzed fish bile using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to semi-quantitatively measure PAH equivalent concentrations (parent compounds plus metabolites) of naphthalene, phenanthrene, and benzo[a]pyrene, which indicates short-term (hours to days) PAH exposure. She also prepared liver, muscle, and gonad tissue samples using the Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) extraction process and applies gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS-MS) to assess concentrations of nineteen PAHs (including 16 considered priority pollutants by the EPA) and their alkylated homologues in fish tissue, which indicates long-term (months) PAH exposure.

Only eight of the fifteen pelagic fish examined yielded enough usable data to draw conclusions. Although Madison is still interpreting her data, her early results suggest that there are higher PAH equivalent concentrations in yellowfin tuna bile than the other seven fish species. These levels were similar to concentrations observed in the benthic golden tilefish, which are considered the highest known PAH equivalent concentrations in the Gulf of Mexico. These preliminary findings represent one of the first indications that pelagic fish species can be significantly affected by PAHs deposited into the Gulf of Mexico.

“Finding similar PAH equivalent concentrations in yellowfin tuna and the golden tilefish was unexpected, because the golden tilefish is a burrowing fish and is strongly linked to sediments, where about 21% of Deepwater Horizon hydrocarbons likely settled,” she explained. “Finding significant short-term PAH concentrations in yellowfin tuna several years later suggests that they are possibly being impacted by contamination sources other than Deepwater Horizon, such as the Mississippi River and the on-going natural oil seeps or small oil spills that frequently occur in the Gulf.”

Her Learning

Madison’s GoMRI work was her first experience conducting toxicology research. Her lab mates, especially Dr. Erin Pulster, taught her a great deal about common toxicological methods and operation of analytical instruments. While her lab work focused on the finer details, she experienced the larger implications of her research through field work. “Catching target pelagic species for our oil spill research just meters away from oil rigs highlighted the connection between my research and the bigger picture,” she said. Attending the annual Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science conference helped her learn from oil spill researchers in other fields and further connect her own findings to the entire ecosystem. “Being part of GoMRI allowed me to gain a holistic perspective on Deepwater Horizon’s short- and long-term impacts on Gulf ecosystems and surrounding communities.”

Madison has an increased appreciation for transferable scientific skills, such as statistics and programming, and for opportunities that improve scientific writing and communication. She hopes to find a career where she can use her background and experiences to synthesize scientific findings and inform practices and policies that protect vulnerable ecosystems from pollution and oil contamination.

Praise for Madison

Dr. Murawski explained that Madison’s Deepwater Horizon research has equipped her with broadened skills sets for investigating key contemporary threats to marine ecosystems, especially related to chemical pollution resulting from acute oil spills. “Her work on pollution levels in large pelagic fishes of the Gulf has opened up new venues of research and provided important new insights into how the Gulf of Mexico functions,” he said. “She has a bright future in marine science and policy, wherever her career takes her.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Madison Schwaab and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the C-IMAGE website to learn more about their work.

By Stephanie Ellis and Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact sellis@ngi.msstate.edu for questions or comments.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2020 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

In April 20, 2010, the Gulf of Mexico had its greatest mishap in record time with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, wherein an estimated 1,000 barrels of oil (peaking at more 60,000 barrels) per day were released into the Gulf for 87 days, for a total of 3.19 million barrels for the entire duration. The ecological impacts of this spill have become one of the subjects of extensive research.

In April 20, 2010, the Gulf of Mexico had its greatest mishap in record time with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, wherein an estimated 1,000 barrels of oil (peaking at more 60,000 barrels) per day were released into the Gulf for 87 days, for a total of 3.19 million barrels for the entire duration. The ecological impacts of this spill have become one of the subjects of extensive research.