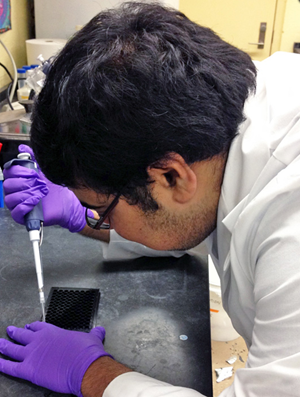

Subham conducts an ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase or EROD assay to measure the activity of the detoxifying enzyme CYP1A1 under PAH exposure. (Provided by Subham Dasgupta)

Subham Dasgupta’s dedication to understanding oil and dispersant toxicology stems from his roots in India. Having grown up in a community where fishes are an important part of the diet, his research assessing oil and dispersant exposure’s effect on fish health has a special importance for him.

“Oil spills can affect marine organisms, including the fish we eat,” he says. “This is particularly important for my country, which is surrounded on three sides by the sea. I hope that my research will help inform responders’ cleanup decisions and uncover new information about dispersed oil’s potential impacts on marine organisms.”

Subham is a marine sciences Ph.D. student at Stony Brook University and a GoMRI Scholar with the project Characterizing the Composition and Biogeochemical Behavior of Dispersants and Their Transformation Products in Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ecosystems. He shares his research and the important lessons he has learned from it.

His Path

As an undergraduate student at Presidency College (now University) in Kolkata, India, Subham was unsure of his direction. It was not until he began an environmental sciences master’s degree that he discovered his love for research. The many paths available to answer scientific questions and the possibility for collaboration across multiple disciplines excited him. His involvement with several research projects near Kolkata led him to pursue a Ph.D. in aquatic toxicology.

“I applied to programs in the United States because the education system and research quality are well-known,” Subham said. He connected with Dr. Anne McElroy, an aquatic toxicology professor with the Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences graduate program. His work in her lab initially focused on analyzing the impacts of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposure on the embryos of Japanese rice fish (also known as the medaka or Japanese killifish Oryzias latipes).

His Work

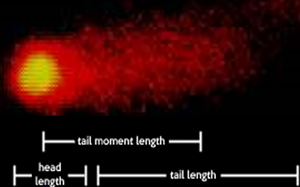

Subham’s comet assay technique measures DNA damage under different oil and dispersant component exposures. Results appear as “comets” such as this, where the “head” of the comet represents nucleoid with intact DNA and the “tail” represents damaged DNA that has migrated out due to electrophoresis. (Provided by Subham Dasgupta)

When McElroy joined a GoMRI-funded research group led by Mississippi State University’s Darrell Sparks, Subham’s research shifted to investigate the toxicity of Corexit 9500 and 9527 dispersants and their major components to sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) embryos and larvae. He evaluated Corexit-exposed larvae and examined the impact of low concentrations of the surfactant DOSS on larvae survival and possible correlation of DOSS and other solvents with DNA damage.

Subham is now investigating potential toxicity amplification in fish under hypoxic conditions combined with Corexit and oil exposure. “Hypoxia is an increasing concern in coastal areas with river discharge,” he said. “River waters carry nutrients from fertilizers that can trigger phytoplankton blooms. The increased microbial activity leads to reductions in dissolved oxygen in the water. The Northern Gulf of Mexico has an expanding area of seasonal hypoxia.” His studies with sheepshead minnow larvae are indicating that Corexit and water-soluble oil components may stimulate an increased production of CYP1A, an enzyme that assists the transformation of PAHs into less-toxic compounds that the fish can expel. However, hypoxic conditions may reduce CYP1A activity, potentially contributing to accumulation of oil and dispersant components in fishes and posing a greater risk to aquatic organisms.

His Learning

Subham (right) poses with Anne McElroy (left) and a high school summer research fellow, who enjoyed working with Subham and McElroy so much that he created matching t-shirts for the group. (Provided by Anne McElroy)

Studying numerous compounds contained in oil and dispersants, Subham has become more aware of different ways to approach an experiment and found that a study’s path is often unpredictable. “You can’t always look at it from the linear perspective that A will lead to B. A might lead to B, C, and D, and it’s exciting how that works out,” he says. Communicating with other researchers has exposed him to new scientific techniques and perspectives that have helped advance his research. “I had good success incorporating some methods I heard about at last year’s Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science Conference into my work,” he said. “There are many ways to look at the same problem, and that is what I love.”

One of the most important lessons Subham has learned from his advisor is that scientific research requires patience. “I’ve never seen her frown or complain, and that showed me that I need to be patient with what I’m doing,” he explains. Experiments can fail as often as they succeed, and he believes that scientists should not view failures negatively. Instead, he focuses on brainstorming new ways to solve problems. “I think focusing on overcoming your failures teaches you something about life,” he says. “You can’t always expect the best – sometimes you have to deal with the worst to get the best.”

Subham’s journey has confirmed for him that students considering a career in science should pursue science because they want to, not because they think they should. “Like all fields, science is full of pluses and minuses, happiness and disappointment, success and failure,” he says. “It’s not as if you come into the field and immediately have success. It’s hard work.” Subham finds that as long as you love your field, the struggles will always be worth it.

His Future

After completing his Ph.D., Subham would like to serve in a post-doc position and continue in academia as a researcher and professor. Ultimately, he wants to return to India and help develop the marine science and toxicology field using his education and experience. “For a country surrounded by water and influenced by a large number of major rivers, the study of aquatic toxicology needs to be better developed. Given the opportunity, I would love to execute my training back in India – hopefully that will happen.”

Praise for Subham

Subham’s advisor, Dr. Anne McElroy, said that he is dedicated to his research and described him as extremely enthusiastic, unfailingly optimistic, and willing to do whatever is required to meet his research goals. “A comet assay technique that Subham adapted for use on sheepshead minnow larvae allowed us to detect direct DNA damage and demonstrate that oxygenated PAHs have similar if not greater genotoxicity than parent PAHs,” she says. McElroy is excited about his future as a scientist, explaining that Subham’s broad interests give her confidence that he will go far.

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Subham Dasgupta and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

Visit the Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Science website to learn more about their work.

************

This research was made possible in part by a grant from BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) to the project Characterizing the Composition and Biogeochemical Behavior of Dispersants and Their Transformation Products in Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ecosystems. The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.