The ocean’s deep-pelagic ecosystem is the largest and least understood habitat on Earth. In the Gulf of Mexico, it was the largest ecosystem affected by the Deepwater Horizon incident. Because there was very limited pre-spill data about deep-pelagic organisms’ biodiversity, abundance, and distribution, it is difficult to determine how oiling may have affected different deep-sea species.

Information about the longevity and age at reproduction of key Gulf of Mexico deep-sea fauna, such as lanternfish or fangtooths, is crucial to determine their vulnerability and resilience to disturbances such as oil spills. However, the depths at which these organisms live and the challenges involved with raising them in captivity or tagging them in the wild make collecting this data difficult.

Natalie Slayden uses ear stones, called otoliths, collected from fish living in Deepwater Horizon-affected waters to study the age and growth of nine Gulf of Mexico deep-sea fish species. Her research can be used to estimate the lifespan and age at which these deep-sea fishes reproduce to determine how quickly a potentially compromised assemblage might be replaced following an environmental disturbance.

Natalie is a master’s student with Nova Southeastern University’s Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences and a GoMRI Scholar with the Deep-Pelagic Nekton Dynamics of the Gulf of Mexico (DEEPEND) Consortium.

Her Path

Natalie developed an appreciation for marine environments at an early age. Growing up near the Appomattox River in Virginia, she spent her childhood swimming and using kite string and doughballs to fish for catfish on her grandparents’ houseboat. Her family often traveled to North Carolina’s Outer Banks, where they spent their days searching for fish, blue crabs, and hermit crabs in tide pools formed during high tides. These formative experiences inspired Natalie to pursue a biology undergraduate degree with a marine biology concentration at Old Dominion University. During that time, she participated in several research projects, including a Belize study abroad program researching coral reef ecology, a Cayman Islands internship researching lionfish diets, and a project with Dr. Mark Butler’s marine ecology lab investigating how climate change could affect the transmission of the Caribbean spiny lobster disease, PaV1 (Panulirus argus Virus 1).

When Natalie began her marine biology master’s studies at Nova Southeastern University, she volunteered in various labs searching for projects that included meaningful research. One of her volunteer experiences was with Dr. Tracey Sutton’s Oceanic Ecology Lab, and the numerous deep-sea questions and research focuses intrigued her. She joined his lab as a graduate student working on his GoMRI project investigating deep-sea fish’s resiliency to disturbances such as oil spills. “Deep-sea research appealed to me because of how rewarding it can be,” said Natalie. “While I’m currently studying the age and growth of Gulf of Mexico deep-sea fishes, there will always be an avenue for research [related to the deep sea].”

Her Work

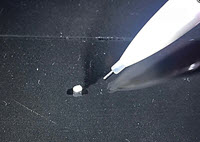

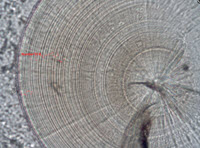

Otoliths, located in the fish’s cranium, assist with hearing and balance and provide a natural, chemical tracer representing an organism’s lifetime record of environmental exposures. Because the otoliths Natalie works with are as small as a grain of sand, she removes them using fine tools and photographs and measures them using a microscope-mounted camera. She then grinds and polishes the otoliths to reveal rings that can help her determine the fish’s age, similar to tree rings. She estimates each specimen’s age as a range based on the unit (days, years, etc.) that the rings likely represent for each species. “The otolith rings can mean different things for each fish and could be counted as days, years, or even represent feeding events or different life stages,” explained Natalie. “So far, it seems that the rings in most of the species I am studying may represent different life events and feeding.”

When interpreting a fish’s age using life events, Natalie measures the fish’s length and compares it to the length at which larval fish swim to depth. Then, she looks for evidence that indicates this event in the otoliths (typically seen as a change in the rings’ darkness or width). She also looks for evidence of life events such as undergoing a transformation or, if a fish is a hermaphrodite, a change in sex. When interpreting the otoliths for feeding events, dark rings can represent starvation while lighter rings indicate a food event or digestion. However, interpreting a fish’s age based on feeding varies between species. For example, lanternfish migrate to the surface each night to feed and acquire daily rings that represent both one day and a meal. Fishes that feed less frequently are more complicated to age, and Natalie depends on existing data about their feeding habits to estimate age.

The data that Natalie has collected on fish age can help estimate the average lifespans of different deep-sea species, which helps her interpret their resilience to disturbances. Species who more quickly repopulate due to their short life spans may also more quickly rebound from environmental disturbances like oil exposure. The data on fish age and lifespan from Natalie’s research will become input parameters for models that estimate how long their recovery from disturbances may take. “In an environment disturbed by an oil spill, fish populations with individuals that have a shorter lifespan would likely recover the fastest,” said Natalie. “If we know how old these oil-exposed fish are using the data recorded in their otoliths, it can help us understand how long the oil may have effects on populations.”

Her Learning

Natalie named DEEPEND’s DP06 research cruise in 2018 as her most rewarding experience participating in GoMRI research and recalled her excitement at seeing deep-sea organisms first-hand as they came out of trawling nets. She felt fortunate to work alongside scientists from diverse fields and learn new skills from other researchers, especially a team that often discovers new organisms. “The researchers were nice, welcoming, and fun to be around, and the crew was just as excited about our research as we were,” she said. “The cruise taught me the importance of comradery and simply being good to one another.”

Natalie presented her research at the 2019 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science conference and plans to present an updated talk at this year’s event. “I am incredibly thankful to be a member of the GoMRI science community,” she said. “It is an honor to be able to work alongside and learn from scientists who are at the top of their fields.”

Natalie is confident that the skills she learned working in Dr. Sutton’s lab will help her transition to the workforce. She also believes that gaining diverse skills and having a multidisciplinary background will expand her future options and plans to take additional course work in cyber security and computer programming after graduating. “It’s ok to be unsure of what exactly you want to do and to change the subject matter of your work,” she said. “I went from studying Caribbean Spiny lobsters to studying deep-sea fishes living a mile below the surface. There is no limit!”

Praise for Natalie

Dr. Sutton explained that Natalie represents everything that his lab and the GoMRI program promotes, especially scholarship, leadership, and character. He described her as being scientifically fearless, attacking the research with gusto. “She learned the intricacies of ageing fishes, then applied them to a group of fishes who are not only quite technically difficult (having small, aberrant otoliths) but also quite difficult to interpret, as they live below the daily signals of sunlight,” he said.

Dr. Sutton also praised Natalie’s leadership skills when she leads the lab’s daily operations and, by extension, the efforts of numerous DEEPEND research projects. He explained that she handles all things with grace and generosity and takes requests with a smile. “The word with Natalie is trust – when she handles a task, you know it will be done well and on time,” said Dr. Sutton. “She speaks softly and slowly but thinks quickly, creating a joyful, positive vibe in the lab for which I am extremely grateful.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Natalie Slayden and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the DEEPEND website to learn more about their work.

By Stephanie Ellis and Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact sellis@ngi.msstate.edu for questions or comments.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2020 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).