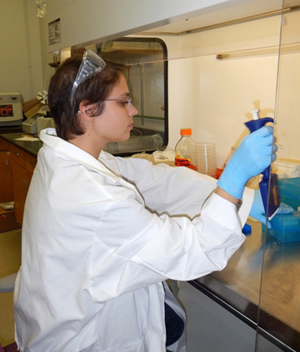

Sarah transfers DNA samples from single-cell organisms in the lab at University of West Florida. (Photo credit: Richard Snyder)

To show how the Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacted the Gulf of Mexico, Sarah Tominack is going back to basics.

She feels that for scientists to quickly identify the Gulf in distress, they must have a better picture of what “normal” looks like, particularly for microscopic single-celled organisms at the marine food web base called archaea.

Understanding these tiny creatures, which are at the whim of their environment because they do not have the ability to move, could provide additional insight about what happens when pollutants enter their world. “We really don’t know much about how they work or why they live where they live,” explains Sarah, so she is working to uncover their everyday dynamics.

Sarah is a GoMRI scholar working with Deep-C scientists at the University of West Florida (UWF). Here she describes her process and what she has discovered so far.

Her Path

Sarah collects sediment samples for DNA analysis on board the Florida Institute of Oceanography R/V Bellows. (Photo Credit: Richard Snyder)

Coming from a family of science-minded individuals, Sarah loved to explore the world around her. “Running through the woods as a kid, I was always interested in why I found certain critters where I found them,” says Sarah. “As time went on, I began to realize that everything was somehow related.” Understanding that all living things were linked gave her a thirst for knowledge in a variety of subjects. She went from class to class, loving every new subject more than the last, culminating with an undergraduate degree from the University of North Alabama in environmental biology with two minors—chemistry and Spanish—because she could not make up her mind which subject she enjoyed most. Always at the top of her list, however, was seeking information about relationships in nature.

Sarah’s graduation in December of 2012 coincided perfectly with the opportunity to join Wade Jeffrey and Richard Snyder at UWF’s Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation. The pair were co-Principle Investigators on a Deep-C research project seeking to establish baseline information on microbial and biogeochemical processes in the northeastern Gulf. The prospect of working with biologists, chemists, and ecologists to better understand the marine environment was a perfect fit for her interests.

Her Work

Sarah describes the importance of microbes like archaea using a pyramid analogy. As the base of the pyramid, the microbial world’s structure, stability, and function affects every life level above it—even humans. With this in mind, her particular research does not focus on oil’s impacts on microbes, but on understanding their system when it is healthy. “If we do not have a good characterization of the dynamics of microbial populations before a catastrophe,” explains Sarah, “we cannot predict what will happen during and after a catastrophe.”

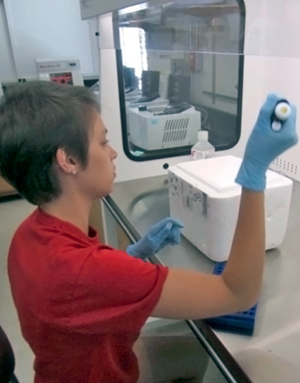

Sarah processes samples for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of Archea DNA sequences. (Photo credit: Richard Snyder)

Sarah joined six research expeditions to collect data. She went out in different seasons, tracing the same path three days in a row each trip. Her team deployed equipment that obtained samples while measuring temperature, salinity, and oxygen levels. Back in the lab, Sarah extracted the archaea from the samples and used bioinformatics—the computational side of DNA analysis—to learn about how the different species of archaea relate to one another and how natural fluctuations in the Gulf impact their life cycle.

She is finding that archaea populations living in the nearshore coastal waters and deep waters (below 100 meters) stay fairly stable throughout the seasons. However, archaea living near the water surface of the open Gulf disappear during the hot summer months. She hypothesizes that because the tiny creatures cannot swim, they die out from starvation as brilliant blue offshore surface water that is low in nutrients takes over the continental shelf. Then, the population reestablishes itself in the winter months when the water cools and archaea churn up from the bottom as the water layers naturally mix again.

Her Learning

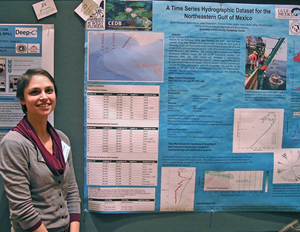

Sarah says working with Deep-C has improved her as a scientist on every level. Not only has she become comfortable with collaborative efforts between different disciplines, but also she has learned how to present her findings to other researchers. Conferences provided opportunities to share her research via talks and posters and to network with other scientists in related fields. She says it is just as important to discuss failures as successes in these instances, because “you never know who will help you solve the problem.”

Sarah found the Student Symposium hosted by Deep-C particularly meaningful, giving her a chance to practice her presentation skills in front of friendly faces. In addition, the many opportunities provided to interact with senior scientists helped her become comfortable picking their brains. Calling it an “irreplaceable experience,” Sarah says, “It was set up in a way that I could ask all of the questions I never knew I had.” Instead of finding senior scientists intimidating, she discovered that they were more than willing to lend an ear—or a hand.

Her Future

Sarah operates the computer station for oceanographic data and water column sample collection on board the Florida Institute of Oceanography R/V Bellows. (Photo credit: Richard Snyder)

Sarah just completed her master’s degree in biology. Before pursuing a Ph.D., she wants to experience more of the world. To that end, she has committed to spend a year working with Habitat for Humanity through the AmeriCorps program. “I am ready to broaden my horizons as a person and gain new perspectives as a scientist in the community,” she explains. In the spring, Sarah will also teach an undergraduate course in Aquatic Botany at UWF.

Praise for Sarah

Sarah’s advisors, UWF biologists Richard Snyder and Wade Jeffrey describe her as highly motivated, enthusiastic, dedicated, and competent. Snyder recalls that Sarah was very hard on herself in the beginning of her graduate program, concerned that she would not be able to learn shipboard collection procedures and that seasickness might incapacitate her. “As it turns out, she was one of few that did not get sick and quickly became the reliable ‘go to’ person on board,” he remembers. “She ended up being one of our very best in the scientific crew.”

Sarah Tominack shares her research at the GOMRI Oil Spill Research Conference Mobile, Alabama in January 2014. (Photo credit: Richard Synder)

Sarah’s mastery of molecular biology lab processes quickly became apparent on shore as well. She took the lead, learning computer routines for DNA sequence data processing and analysis and then teaching it to other students. Snyder said, “By her own initiative, she became the in-house expert on not only the bioinformatics tools needed, but also the management, plotting, and analysis of oceanographic data and multivariate statistical analysis—no small feats in themselves!” Jeffrey concurs, “She showed great initiative in taking on much of the computer work and bioinformatics required of our projects.”

Though Sarah’s advisors are excited for her as she goes off to her next adventure, they will miss her greatly. Snyder summed up what a great asset she has been, saying that in his eyes, Sarah is a “master’s student with Ph.D. level competence.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Sarah and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

(Photo credits: Richard Snyder)

Visit the Deep-C website to learn more about their work.