The Alabama Center for Ecological Resilience (ACER) blog hosted a series of posts discussing the meaning behind various terms and concepts that are important to ACER research.

The Alabama Center for Ecological Resilience (ACER) blog hosted a series of posts discussing the meaning behind various terms and concepts that are important to ACER research.

Gary Finch Outdoors produced a series of videos highlighting various aspects of the Ecosystem Impacts of Oil and Gas Inputs to the Gulf (ECOGIG) program, its science, and the important partnerships necessary to make ECOGIG successful. Many of these videos were used by local PBS affiliates in Gulf coast states and were available through the ECOGIG website and YouTube. All videos listed below were developed and produced by Finch Productions, LLC.

What Does ECOGIG Do? (PBS Part 1) (2:20)

Scientists aboard the research vessels R/V Endeavor and E/V Nautilus briefly describe the nature of ECOGIG research.

Collaboration Between Nautilus and Endeavor Tour (PBS Part 2) (2:06)

ECOGIG scientists discuss the research they are conducting on a recent cruise aboard the R/V Nautilus and E/V Endeavor.

ECOGIG R/V Atlantis/ALVIN Cruise: March 30-April 23, 2014 (2:00)

Researchers describe the crucial importance of ALVIN dives in assessing the ecosystem impacts of the Deepwater Horizon explosion.

Deep Sea Life: Corals, Fish, and Invertebrates (4:30)

Dr. Chuck Fisher describes his research examining the fascinating and long-lived deep sea corals impacted by effects of the Deepwater Horizon explosion.

The Eagle Ray Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) News Piece (5:12)

ECOGIG scientists use the Eagle Ray AUV (autonomous underwater vehicle) to map the seafloor and get visuals so they can better target their sample collecting for study. The National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology (NIUST) provides the submersible.

(Full Length)

(Shortened News Piece)

Food Webs in the Gulf of Mexico (4:30)

ECOGIG scientists Jeff Chanton and Ian MacDonald, both of Florida State University, explain their complementary work exploring the possibility that hydrocarbons from oil have moved into the Gulf food web. Chanton, a chemical oceanographer, tells of a small but statistically significant rise in fossil carbon, a petrochemical byproduct of oil, showing up in marine organisms sampled from Louisiana to Florida. In addition to the hypothesis that Deepwater Horizon oil might be the culprit, biological oceanographer MacDonald discusses other factors that could also be at play, including coastal marsh erosion, natural oil seeps, and chronic oil industry pollution. This is a Finch Productions, LLC video. For more information, visit ECOGIG.ORG. https://ecogig.org/

Landers Technology Development (4:30)

Most of the area around the Deepwater Horizon spill ranges from 900 – 2000 meters below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. ECOGIG scientists Dr. Chris Martens and Dr. Geoff Wheat talk about Landers, a new technology developed at the University of Mississippi that allows scientists to study the ocean floor at great depths. Landers are platforms custom-equipped with research instruments that can be dropped to the exact site scientists want to study and left for weeks, months, or even years to collect ongoing data.

Marine Snow (4:30)

Dr. Uta Passow describes research she and her colleagues Dr. Arne Dierks and Dr. Vernon Asper conduct on Marine Snow in the Gulf of Mexico. Oil released in 2010 from the Deepwater Horizon explosion floated upwards. Some of this oil then sank towards the seafloor as part of marine snow. When marine snow sinks, it transports microscopic algae and other particles from the sunlit surface ocean to the dark deep ocean, where animals rely on marine snow for food.

Natural Seeps – Geology of the Gulf (4:30)

ECOGIG Scientists Dr. Joe Montoya, Dr. Andreas Teske, Dr. Samantha Joye, and Dr. Ian McDonald describe their collaborative research approach while preparing for the Spring 2014 cruise aboard the R/V Atlantis with research sub ALVIN. Long-term sampling and monitoring of natural oil seeps in the Gulf of Mexico, a global hot spot for these seeps, is crucial for understanding the impacts of oil and gas from explosions like Deepwater Horizon.

Remote Sensing & Modeling (4:30)

ECOGIG scientists Dr. Ian MacDonald and Dr. Ajit Subramaniam describe their work monitoring the health of the Gulf of Mexico via remote sensing. Using images from satellites and small aircraft flown by volunteers, MacDonald looks for signs of surface oil, which could be the result of a natural seep, anthropogenic seeps (chronic oil leaks from ongoing drilling operations), or a larger spill like Deepwater Horizon. Subramaniam uses the changes in light in these images to help him understand what is happening below the sea surface, with particular focus on the health of phytoplankton populations that make up the base of the marine food web. This is a Finch Productions, LLC video with additional footage provided by Wings of Care, a nonprofit that assists with volunteer filming operations.

ROVs in STEM Education News Piece (4:30)

ECOGIG’s Dr. Chuck Fisher describes the use of ROVs in researching deep -sea corals in the Gulf of Mexico, and Ocean Exploration Trust’s Dr. Bob Ballard explains the powerful impacts of ROVs in STEM education, as shown during a recent visit onboard the EV Nautilus by members of the Girls and Boys Club of the Gulf region.

(Full Length)

(Shortened News Piece)

Notes from the Field is an educational newsletter created for middle school students that focuses on issues relevant to coastal communities in southeast Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. Exploring topics ranging from periwinkle snails to tropical storms to coastal erosion, each issue includes educational hands-on activities, puzzles, term glossaries, interviews with scientists, and scientific research.

Click the newsletter covers below to download the PDF!

Phytoplankton and bacteria in the northern Gulf of Mexico interact closely at the food web base and provide vital food and nutrients to marine life at higher trophic levels. During the Deepwater Horizon incident, these pervasive organisms played an important role in oil bioremediation before and after the application of chemical dispersants, which broke up surface slicks into smaller droplets and enhanced microbial degradation. Samantha “Sam” Setta, who recently completed her master’s degree, used molecular-level techniques to learn how oil and dispersant exposure affects the abundance of and interactions between Gulf bacteria and phytoplankton.

Sam recently graduated from the Texas A&M University at Galveston’s Marine Biology Department and was a GoMRI Scholar with the Aggregation and Degradation of Dispersants and Oil by Microbial Exopolymers (ADDOMEx) consortium.

Her Path

Sam’s interest in a scientific career was sparked by a high school aquatic science class that emphasized marine science and conservation. As a freshman at the University of Texas at Austin, she changed her major from chemistry to biology to physics and ultimately settled on marine biology with a focus on freshwater.

“Growing up in Austin, I was surrounded by parks, lakes, and natural springs that influenced my thinking of the world and led me to an interest in conservation, especially water conservation,” said Sam. She enhanced her undergraduate education by conducting research in Mexico and working with a graduate student at the university’s Marine Science Institute, which provided work experience and insight into graduate student life.

However, Sam was still unsure about pursuing a graduate degree and decided to explore different fields to pinpoint her passion. She worked as a research technician on algal biofuel in Texas and later as a research associate with Dr. Brian Roberts studying the Deepwater Horizon’s effects on Louisiana salt marsh vegetation and biogeochemistry. The oil spill research inspired her to pursue graduate school, and she began her master’s studies with Dr. Antonietta Quigg at Texas A&M University at Galveston investigating the spill’s effects on microbial community composition.

Her Work

Phytoplankton are microscopic photosynthesizers that transform atmospheric carbon dioxide into food for grazers and other microscopic heterotrophs. Bacteria then recycle the used carbon into a form that heterotrophs can eat again, starting a microbial loop of recycling and reusing organic carbon. Sam’s research as a master’s student was to learn how oil and dispersant may have affected these microbial interactions.

Sam and her colleagues incubated Gulf of Mexico microbial communities with different oil and oil plus dispersant concentrations in large tanks that mimicked conditions around the spill area. She extracted DNA from bacteria in tank water samples, amplified identifiable DNA regions using polymerase chain reactions, and measured and recorded nucleotides using DNA sequencing techniques. Sam is using the sequencing data to characterize the composition of bacterial and phytoplankton communities under different exposure scenarios.

Samantha is now a Ph.D. student at the University of Rhode Island and continues her oil spill research in her free time. She is currently analyzing the bacteria-phytoplankton interactions for each exposure using a network analysis that correlates community composition over time under different oil and dispersant exposures. Her findings will ultimately identify taxa that play a key role in oil bioremediation, their correlation with certain phytoplankton and other eukaryotic organisms, and how oil and dispersant exposure change these taxa.

“Highlighting the key players that respond to spilled oil will help better direct future studies and oil spill mitigation,” explained Sam. “This information can be used to target key taxa in other laboratory studies and provide more information to policy makers on the pros and cons of using dispersant in the event of an oil spill.”

Her Learning

Sam’s research provided her with frequent experience working in a collaborative environment. She described her time with Dr. Quigg’s group as encouraging and enriching, “I found that the tank experiments we did once a year with the entire research consortium were the best time to collaborate and get to know the research everyone else was doing as part of the project. Everyone involved in the ADDOMEx consortium has been very supportive.”

Her Future

Sam recently began Ph.D. studies in oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. She suggests that students use their time in graduate school to learn where their interests lie before committing to a specific scientific career.

Praise for Samantha

Dr. Quigg described Sam as a student who is smart, determined, and fun to work with. She explained that despite Sam’s complex master’s research for the ADDOMEx consortium and her tremendous determination and ability to work well with others made her project a success. “Sam was one of those students who you meet and immediately know they will be both a great scientist and colleague,” said Quigg. “Her research required her to work on the cutting edge of a variety of disciplines, and she rose to the challenge and even finished her master’s in two years. I look forward to watching her continue to develop her craft as she starts her Ph.D. at the University of Rhode Island this fall.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Samantha Setta and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the ADDOMEx website to learn more about their work.

By Stephanie Ellis and Nilde Maggie Dannreuther. Contact sellis@ngi.msstate.edu for questions or comments.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2018 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

The deep-pelagic habitat (200 m depth to just above the seabed) is the largest habitat in the Gulf of Mexico, yet we know very little about it compared to coastal and shallow-water habitats. Our limited understanding of this major marine habitat makes it extremely difficult to assess the effects of disturbances such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Travis Richards seeks to better understand the structure of deep-pelagic food webs by tracing the energy flow from the food web base through higher trophic levels. His research will help expand our understanding of the deep-pelagic habitat and serve as a reference point for future studies and response efforts.

Travis is a Ph.D. student at Texas A&M University at Galveston’s Marine Biology Department and a GoMRI Scholar with the Deep-Pelagic Nekton Dynamics of the Gulf of Mexico (DEEPEND) consortium.

His Path

Travis discovered his interest in biology through the many scientists and science educators in his family who exposed him to diverse habitats and species through frequent camping, fishing, and hiking trips. His family’s travels took him to sites across the United States, including several trips to the Gulf of Mexico coastline. During his undergraduate and graduate career, he explored a variety of marine ecology opportunities and developed a specialization in marine food webs. He had just completed an ecology and evolutionary biology master’s degree at Florida State University when Dr. David Wells at Texas A&M University at Galveston contacted him about a Ph.D. student position researching deep-sea food webs. He eagerly accepted and joined Wells’ lab team working on the DEEPEND project.

Travis explained that the immersive outdoor experiences of his childhood have become a large part of his identity and are a driving force behind his research interests. “Those transformative experiences give conducting research on marine Gulf of Mexico organisms a personal significance,” he said. “I now have a career pursuing a field that interested me since childhood and contributing to our understanding of an ecosystem that played a significant role in my life.”

His Work

Travis helps collect deep-pelagic organisms using a Multiple Opening and Closing Net with Environmental Sensing System (MOCNESS) that is towed from surface waters to 1500 m depth. He analyzes natural chemical tracers called stable isotopes (variants of chemical elements that have a distinct signature as they transfer from prey to predator) in different organisms’ muscle tissues to identify their position within the food web. He can then piece together the food web’s structure to trace the initial food source and document the natural flow of energy through the food web.

Travis will use the data to describe variation in food web structure, identify the number of deep-pelagic trophic groups with different functions, and determine how much deep-pelagic organisms contribute to the diets of demersal (near the seabed) and epipelagic (surface to 200 m depth) predators. So far, Travis has observed that deep-pelagic food webs are more complex and nuanced than researchers have previously thought. His preliminary results indicate that the food web’s structure varies both seasonally and across horizontal and vertical spatial scales. Researchers can use this information to make better predictions about the ways that removal of targeted species by fisheries or disturbances such as oil spills will affect the food web and the greater pelagic ecosystem.

His Learning

Travis has learned that productivity matters to success in academia. One must always make progress on some aspect of their research, and there is always a paper that needs work or an experiment that can be set up. He said that seeing the contributions of one’s research is a motivating reward for the hard work. “I’m continually impressed with the research being conducted within the different GoMRI funded projects. When you attend a GoMRI meeting, you get a real sense for how much we’re learning about the Gulf of Mexico. It’s exciting to know that our work is contributing to a new and more complete understanding of the Gulf.”

One of Travis’s most memorable experiences working with the DEEPEND consortium is conducting field work – a rare opportunity due to the challenging logistics and expensive nature of deep-sea sampling. “You never know what you’ll bring up in the nets,” he said. “With each research cruise, I’ve been able to see incredibly unique organisms, such as anglerfishes, lanternfishes, and cephalopods, that I never imagined I’d get to see in person.”

His Future

Travis hopes to conduct research as a post-doc and eventually take a position at a liberal arts college teaching and leading a small research program. He advises that students considering a scientific career take advantage of every research opportunity available to them, even those not focused on their exact interests. “Do the best possible work you can at each position you take,” he said. “Once you demonstrate your ability to perform well at a variety of positions, more opportunities will start to open up for you.”

Praise for Travis

Dr. Wells commended Travis’ commitment to leading the deep-sea trophic ecology component of the project’s research, noting that he often puts in extra time to make his research responsibilities his primary task. “He is always willing to participate on cruises and be involved in meetings and present his results,” said Wells. “He recently published his first dissertation chapter in ICES Journal of Marine Science (Trophic Ecology of Meso- and Bathypelagic Predators in the Gulf of Mexico) and is clearly on track to do great things with his project.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Travis Richards and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the DEEPEND website to learn more about their work.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2018 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

Major disturbances such as oil spills can significantly affect populations of vulnerable saltmarsh species, which may result in greater impacts to the overall saltmarsh food web. Shelby Ziegler believes that a better understanding of what saltmarsh predator-prey interactions look like today can help identify changes in the food web following disturbances in the future.

“If we see a big die-off of a certain species after a major perturbation, we need to know what implications that will have moving up or down the food web,” said Shelby. “This research is vital for future generations to better understand and maintain saltmarsh populations and prepare for the effects of events like oil spills.” Shelby is an ecology Ph.D. student with the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill and a GoMRI Scholar with the Coastal Waters Consortium II (CWC II).

Her Path

Shelby became fascinated with biology after dissecting fish and marine animals during a high school marine science class. She knew that when she went to college, she wanted to follow a path that would allow her to go out into the field and work directly with the marine life. During her sophomore year at the College of William and Mary, she conducted undergraduate research in Maine and Washington state that explored how different environmental conditions can potentially affect how communities work, fostering her interest in scientific research.

After completing her undergraduate degree, Shelby worked at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science on the Zostera Experimental Network (ZEN), a large global seagrass network. While investigating seagrass systems across the Northern Hemisphere, she realized that important, seemingly similar coastal habitats can have different functions for marine communities. Shelby accepted a graduate position in Dr. Joel Fodrie’s ecology lab at the University of North Carolina investigating how the Deepwater Horizon oil spill affected the coastal saltmarsh food web with CWC. “There’s a common phrase in North Carolina – no wetlands, no seafood,” said Shelby. “The United States is continuously losing its wetlands – over a football field of marsh per day in Louisiana alone. I want to know what that means for our communities and fisheries economy. It’s a huge question that could take a whole career to understand, but I’m hoping my research can provide a little bit of insight.”

Her Work

Saltmarshes on the Gulf Coast and East Coast are similar in that they are dominated by Spartina alterniflora and its associated fish and invertebrate communities. Shelby collects and reviews Gulf Coast and East Coast saltmarsh baseline data to help construct an ecosystem model that can depict how the removal of different species by a disaster may affect the marsh food web. “The Gulf of Mexico and East Coast have very similar ecosystems but function in very different ways,” she said. “It’s vital to understand how these systems work in general before we can understand how contamination like the oil spill affected the ecosystem or the community.”

The first phase of Shelby’s research examined saltmarsh predator-prey interactions and how they differed between the Gulf and East coasts. She conducted predation assays comparing (1) oiled and unoiled Louisiana sites and (2) oiled and unoiled Louisiana sites and East Coast sites. She collected periwinkle snails from the marsh, tied them to a tether (similar to a fishing rod), and placed them in the marsh overnight for 24 hours. She then counted how many snails were eaten during that time period. This experiment found no differences between oiled and unoiled Louisiana sites (suggesting food web recovery in oiled sites), but showed significant differences between the Gulf Coast and East Coast. “There are a lot of different mechanisms that could potentially drive the differences observed between the Gulf and East Coasts,” explained Shelby. “Those findings led me to focus on not only single predator-prey interactions but also overall food web dynamics and how they differ between the East Coast and Louisiana.”

Shelby’s current research examines the diets of fish living in East Coast and Gulf Coast ecosystems. She reviews and analyzes previously published Gulf of Mexico and East Coast literature to determine baseline food web data. Her literature synthesis indicates that key marsh taxa, such as killifish and fiddler crabs, appear absent in the diets of transient Gulf Coast fish but are found regularly in the diets of the same fish species on the East Coast. Depth marsh flooding caused by tidal inundation may influence these species’ interactions across different regions and, if so, there could be an alternative trophic pathway in the Gulf that affects the amount of energy transient fish obtain from the marsh habitat.

She will combine her current findings with gut and tissue analyses conducted by other CWC researchers to construct an ecosystem model reflecting the baseline dynamics of the saltmarsh food web. They hope future researchers can compare gut contents harvested from saltmarsh organisms following a disturbance with their model and interpret observed dietary shifts to determine which species the disturbance most affected.

Her Learning

Shelby’s work with Dr. Fodrie showed her that asking thoughtful questions is key to conducting solid research. Rather than simply thinking up a research question, Fodrie encouraged her to observe the system being researched and identify the important questions based on what she sees.

Working with CWC allowed Shelby to interact with established scientists from other fields. She believes she gained a little mentorship from each researcher, which she incorporates into her own research and scientific journey. The collaborative effort also taught her the importance of maintaining a balance between supporting the work of others in your project and making sure your own research gets done. During her first semester as a graduate student, Shelby traveled to Louisiana alone to participate in a sampling effort. “I came down not knowing anyone and was integrated into this large group of scientists who all had their own priorities and were trying to get a ton of sampling done in one week,” she said. “I learned that you have to make sure your own voice is heard as a graduate student and stand up for yourself, because your work is just as important as the work that everyone else is doing.”

Her Future

Shelby hopes to focus her career on asking and answering interesting questions and use her findings to push habitat conservation and restoration efforts. She encourages future students to make sure that their chosen field is one that they love. She said, “Graduate school is hard enough even when your research is something that you’re excited and care about, so fight for yourself and your research interests. That includes having a healthy work-life balance – the happier you are with your life, the more productive you’ll be when it comes to your work.”

Praise for Shelby

Dr. Fodrie describes Shelby as a team player in both his lab and the overall CWC project. “Shelby is a real self-starter and hard worker,” he said. “In just her first two years, she’s already spent a dissertations’ worth of time in the field sampling marsh fishes day and night.” He explained that her research is revealing important details about the marsh food web. In particular, her comparative field research and synthesis work demonstrate that – unlike many East Coast marshes – marsh platform fishes are absent from the diets of larger transient fishes in the Gulf of Mexico, revealing new insights about how oil exposure impacts may propagate or attenuate across food webs. He explained that Shelby is also uniquely positioned to export what they have learned about Gulf of Mexico ecosystem responses to oiling and inform the current debate about the potential risks of oil exploration along the East Coast.

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Shelby Ziegler and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the CWC website to learn more about their work.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit https://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010-2018 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

Devika and Chinmay Tikhe floating tabanid larvae out of marsh sediments. (Photo by Claudia Husseneder)

Greenhead horse fly larvae are the top invertebrate predator in the Spartinamarshes along the Gulf of Mexico coastline. Adult and larval horseflies exhibited reduced genetic variation and population declines in oiled marshes after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which suggests that these organisms could be an indicator species for post-spill marsh health. Devika Bhalerao uses DNA analyses to identify organisms important to the larvae’s survival and determine if oiling alters the presence of various organisms in the food web. Her findings will help develop analytical tools that ecologists can use to evaluate the health of tidal marshes.

Devika is an entomology master’s student at Louisiana State University (LSU) and a GoMRI Scholar with the GoMRI-funded project A Study of Horse Fly (Tabanidae) Populations and Their Food Web Dynamics as Indicators of the Effects of Environmental Stress on Coastal Marsh Health led by Lane Foil and Claudia Husseneder.

Her Path

Devika Bhalerao. (Photo by Claudia Husseneder)

Devika’s love for biology began when her mother taught biology to local children in Devika’s childhood home of India. Devika discovered a more focused interest in molecular biology and genomic research while studying as a microbiology undergraduate student at Pune University in India. She gained more genomics experience through the Pune University microbiology master’s program where she used metagenomics to decode the microbiome of the rural Indian population.

Devika attended a presentation about using metagenomics in insect systems given by Chinmay Tikhe, a Ph.D. student in Dr. Claudia Husseneder’s LSU Agricultural Center lab. She contacted Husseneder to learn more about their project and the use of metagenomics to describe the food web of horsefly larvae in Louisiana marshes. “The prospect of using the latest techniques such as next-generation sequencing and metagenomics bioinformatics to figure out how the marsh ecosystem functioned made me excited about this research,” she said. Devika joined the Husseneder lab in spring 2015 as an entomology master’s student.

Her Work

A greenhead horse fly larva. (Photo by Claudia Husseneder)

Devika analyzes the greenhead horse fly larval food web to identify organisms in marsh soil that are important for sustaining this top invertebrate predator. She extracts DNA from the larvae’s gut contents and the surrounding sediments from oiled and unoiled marshes and multiplies a specific DNA region called the 18SrRNA gene using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification technique. She then applies next-generation sequencing to the 18SrRNA gene and compares the resulting sequences to a gene database to identify the organisms present in the gut contents and sediment. This information helps her analyze which organisms in the marsh soil are important for sustaining the greenhead horse fly larvae.

An adult greenhead horse fly. (Photo by Claudia Husseneder)

Devika’s research has shown that most species that are present in the larvae’s gut contents belong to insect and fungi families. Her next steps will compare food webs from oiled and unoiled areas to identify if any food web components are missing from oiled marshes. She and her colleagues will use the bioindicators that she identifies to develop a cost-efficient and user-friendly PCR tool capable of determining marsh health.

“My research is the first study of an apex invertebrate predator food web in coastal Spartina marshes with the purpose of identifying the food web’s key elements,” said Devika. “Since greenhead horse flies are associated with Spartina marshes spanning from Texas to Nova Scotia, this study could develop techniques that can monitor the health of coastal marshes across the entire eastern United States.”

Her Learning

Working in Husseneder’s lab taught Devika how difficult it can be to collect larvae in the field. The collection process requires the entire team to devote considerable amounts of time, diligence, and patience to processing many buckets of sediment for only a few larvae. She considers attending the 2017 Benthic Invertebrates, Metagenomics, and Bioinformatics (BITMaB) workshop organized by GoMRI researcher Dr. Kelley Thomas to be the greatest advantage she experienced as a member of the GoMRI scientific community. “The workshop was a game changer in my research,” she said. “I could use the techniques I learned at the workshop to conduct the bioinformatics of my study myself. In my pursuit to acquire advanced molecular techniques, learning to use Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) techniques was the cherry on the cake.”

Devika standing by her poster at an entomology conference. (Provided by Claudia Husseneder)

Devika has won several awards for her poster and oral presentations, including the 2016 International Congress of Entomology’s Graduate Student Poster Competition award for ecology and population dynamics and a travel award for the LSU Coastal Connections Competition. “The presentation that won me the travel award was extremely challenging, because I had to explain my entire research in three minutes in layman’s terms using only two slides without animation,” she said. She also won the Outstanding Masters Oral Presentation Competition at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Branch of the Entomological Society of America. “This award was memorable because later at an informal meeting one of the judges commended me on my presentation and said that it stood out,” recalls Devika.

Her Future

Devika plans to pursue a Ph.D. program that uses her molecular biology skills. She advises students considering a career in science to find ways to expand their skill sets. “Keep updating your current skill set and acquiring new skills in your field and stay abreast of the latest research in fields besides your own,” she said. “It can open avenues to apply your skill sets in new systems.”

Praise for Devika

Husseneder described Devika as a bright and dedicated student with a knack for figuring things out – a perfect fit for a project handling massive amounts of data and statistics. Even after the BITMaB workshop ended, Devika continued teaching herself how to use the complex statistics associated with environmental metagenomics, which she shares with students from other departments. She also teaches undergraduate students and fellow graduate students how to use DNA sequencing to identify arthropods found in marshes. “Devika is an invaluable part of our team,” said Husseneder.

Devika (middle row, center) and Husseneder (middle row, far right) pose for a group photo with their research team. (Photo by Claudia Husseneder)

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Devika Bhalerao and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

************

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

© Copyright 2010- 2017 Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) – All Rights Reserved. Redistribution is encouraged with acknowledgement to the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). Please credit images and/or videos as done in each article. Questions? Contact web-content editor Nilde “Maggie” Dannreuther, Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University (maggied@ngi.msstate.edu).

Adam Boyette retrieves a glider on the deck of the R/V Point Sur, where he served as chief scientist on the three-day cruise examining the impacts of the Bonnet Carré spillway opening. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Microscopic organisms called plankton, an important component of the marine food web, congregate in the freshwater-laden coastal waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Adam Boyette wants to learn more about how and where these plankton live to better understand how an oil spill or other disaster might impact their populations.

He is collaborating with other scientists to show how the near-coastal environment interconnects with the larger world around it.

Adam is a GoMRI Scholar with CONCORDE working towards a Ph.D. in marine science at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM). He discusses his journey from the Mississippi Delta to the coastal Gulf he now calls home.

His Path

Adam stands by on the deck of the R/V Point Sur to retrieve the CTD rosette. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Adam grew up in a rural town at the heart of the Mississippi Delta, an area made famous by Muppets-creator Jim Henson and blues music. He spent his childhood outdoors collecting insects and snakes, fishing, and exploring the Delta’s rich ecology.

His first visit to the Florida panhandle at age eight sparked a life-long love of the ocean that would eventually steer his future.

Adam did not begin college immediately after high school. Instead, he worked on Mississippi River tow boats and in catering kitchens, discovering new interests and skills in every job. He would earn a bachelor’s degree in marine biology at USM more than ten years after he graduated from high school, immediately complete a master’s degree in marine science, and then move on to his Ph.D.

“I had this unfulfilled yearning to do something meaningful, something where I could contribute,” Adam said, explaining that living through the one-two punch of Katrina and the oil spill deeply affected him. “You want to be part of something bigger than you are. I knew without a doubt that I wanted to be a marine scientist.” Adam joined several research cruises while working as a graduate assistant for ECOGIG co-principle investigator Vernon Asper, including the successful effort to rescue the downed AUV Mola Mola. Familiar with GoMRI’s mission, he jumped at the chance to join CONCORDE director Monty Graham’s lab when the consortium formed in 2015.

His Work

Adam takes notes in the R/V Point Sur’s lab while his FlowCam analyzes samples. (Photo by Alison Deary)

Adam studies the thin layers of plankton common in the coastal Gulf of Mexico water column. He measures the plankton’s photosynthesis processes to better understand their uptake and primary production rates of carbon. He also investigates how frequently other organisms, namely predatory microzooplankton, graze on these plankton concentrations. This information will help researchers understand how pollutants like oil move through the area and what living creatures they impact.

Adam collects seawater within the Mississippi Bight, a coastal environment dominated by river water plumes that mix and merge with the salty Gulf. He has joined other CONCORDE scientists on three larger research cruises and sampled on his own in small crafts. “When I’m not actually on a research cruise, I’m either preparing to go on one or analyzing data from a previous one,” he laughed.

Adam determines carbon uptake rates in his samples using an incubator called a photosynthetron, which simulates the in situ light environment and uses the resulting vertical light gradient to measure photosynthetic rates. He uses this information to calculate plankton’s carbon production and uptake and to estimate changes in phytoplankton abundance and growth over a 24-hour period.

Adam works on dilution experiments during the early morning hours of a cruise. (Provided by Adam Boyette)

He also conducts experiments to examine grazing rates for microzooplankton feeding on phytoplankton. Then, he runs the samples through a particle imaging device called a FlowCAM to identify organisms in the water, allowing him to determine how many and which plankton and predatory microzooplankton species live in his study area.

Adam uses this information to understand the dynamics of nearshore microbial populations during various seasons. His calculations will be incorporated into a large ecological model that CONCORDE scientists are creating to represent the physical, chemical, and biological processes in the nearshore environment. “My motivation is to understand the connectivity between all things, to show how delicate the interplay is between the world we see and the microbial world,” he explained. “It’s a personal fascination.” Adam’s raw data collected through his CONCORDE research are available through the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Information and Data Cooperative (GRIIDC).

His Learning

“As Dr. Graham’s student, I’ve learned a lot about working collectively to achieve a common goal,” Adam said. “He’s provided wonderful leadership opportunities for emerging scientists to learn and grow.” One such opportunity came earlier this year, when Adam served as the chief scientist on an emergency three-day multi-consortia cruise to study the Bonnet Carré spillway opening, an action taken to protect New Orleans from rising Mississippi River floodwaters that sent millions of gallons of freshwater into the northern Gulf. He and other GoMRI scientists attending the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science Conference discussed how the unusual event might impact their study areas and planned the cruise.

Adam and fellow graduate student Naomi Yoder teach Pontchartrain Elementary students about nearshore ecology during an Earth Science Day event. (Photo by Stephanie Watson)

The cruise included scientists from CONCORDE, DEEPEND, ECOGIG,CARTHE, and ACER. Adam took pleasure in seeing the process through from its somewhat chaotic inception to a highly organized research event, drawing on his experiences working in professional kitchens to keep everything running smoothly. The array of cross-disciplinary GoMRI scientists also helped make the project a success. “The most important thing I learned from this experience was to let go,” Adam said of his chief scientist position. “Put your trust in people and don’t try to be in control of everything. Instead, work with everyone and utilize their expertise – these people are here for a reason.”

His Future

Adam plans to finish his doctoral program in May 2018. He wants to continue researching plankton ecology using technologies such as satellite imaging and the FlowCam. His dream is to become an ongoing water quality project manager working for government agencies such as NOAA or the EPA or in a postdoctoral role at a university. “The oil spill has really shown the importance of long-term datasets,” Adam said.

Adam and fellow USM student Liesl Cole work in the R/V Point Sur’s highly secure radioisotope lab (known as the “rad van”) during the CONCORDE Spring Campaign. (Photo by Heather Dippold)

Praise for Adam

Monty Graham serves as both CONCORDE’s principle investigator and the Director of USM’s School of Ocean Science and Technology. He stated, “I can attest to Adam’s maturity, leadership potential, technical skills, and motivation and am thrilled that he is being recognized for his efforts.” Graham called Adam a critical member of the CONCORDE project, “He has been the student that his peers look up to, and a student that my research colleagues seek for advice. He pursues every opportunity to increase his knowledge within his chosen field, and has learned new technologies that are going to be applied widely in our studies.”

Graham explained that Adam shines in leadership roles, receiving “stellar reviews” from everyone involved in the Bonnet Carré cruise. “He has led his fellow students through trainings and scientific discussions and he is respected by his peers and senior scientists alike,” said Graham. “He is an excellent addition to the GoMRI Scholar program and is the definition of student success.”

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Adam Boyette and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals. Visit the CONCORDE website to learn more about their work.

************

This research was made possible in part by a grant from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

Sargassum seaweed is often found floating freely in both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Take a closer look and you will find a community of organisms thriving around these floating islands. Unfortunately, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill threatened these open-ocean habitats and the animals that depend on them. To assess how pelagic Sargassum was impacted by the oil spill, researchers from the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) set out in the fall of 2010 to collect samples.

Classroom Activity: Habitat Balance

Sargassum is a floating brown algae that is common to the northern Gulf of Mexico. They provide critical habitat for many marine species and are therefore critical to the food web. In this activity, students will learn about its importance and how it was affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Sargassum_Floating Nurseries – PDF 1.1MB

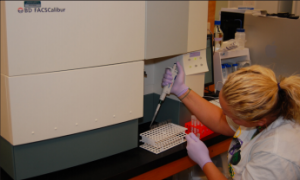

A flow cytometer is used to analyze bacteria, archaea and viruses collected after the oil spill. Photo credit: DISL

Scientists across the Gulf of Mexico, with support from NGI, are evaluating the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the health of the marine ecosystem. To understand the effects on key elements of the marine food web, one Dauphin Island Sea Lab scientist is comparing microbial samples taken before the oil spill to samples that were exposed to Deepwater Horizon oil.

Classroom Activity: Food Web Wipeout

Food webs demonstrate complex feeding relationships among species in an ecosystem by combining several food chains. Scientists use food webs to demonstrate the fragile and interconnected nature of an ecosystem. This activity demonstrated the complexity of a food web and what can happen when one component of a food web is altered.

Microbes and the Marine Food Web – PDF 1.1MB

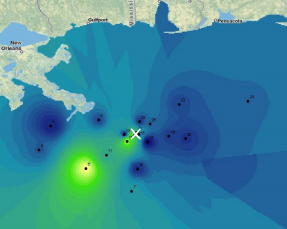

This map shows the radiocarbon content of sediments on the seafloor of the Gulf. The more bright colors represent less radiocarbon; indicative of oil input. You can clearly see the trace of the oil plume to the southwest of the spill site (marked with an x). Image credit: Jeff Chanton, FSU

The effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico are, for the most part, still unknown. Florida State University has developed an integrated study of the impact of oil on the coastal and ocean marine ecosystem of the Gulf of Mexico, including the northern West Florida Shelf, extending from the Big Bend Region west to Louisiana. They are investigating the effects of the spill on coastal ecosystems with a particular emphasis on changes in the food webs that support major commercial and recreational fisheries in the Gulf and in locating oil on the seafloor.

Classroom Activity: You Are What You Eat

Students will investigate a food chain and explore how what an animal eats and where it lives leaves permanent chemical marks on them. The chemical marks can be analyzed by scientists and allow them to learn about the animals life history.

Florida to Louisiana_Tracing the Oil – PDF 1.2MB

An Integrated Ecosystem Assessment incorporates human, biotic, and physical interactions of an ecosystem that result from human and natural system disturbance. Image Credit: DISL

For several years now, a team of scientists from research institutions across the Gulf coast has worked together to develop an Integrated Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) model for the northern Gulf of Mexico. Researchers, including oceanographers, ecosystem modelers, and population ecologists came together shortly after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to set up the framework for examining the ecological impacts of the disaster.

Classroom Activity: Ecosystems

Scientists study ecosystems by learning about their living and non-living components and how they are connected to one another. In this lesson, students will discover what an ecosystem is and explore one, either in person or virtually, to better understand all of the components.

Ecosystem Modeling Framework – PDF 1MB